Hi everyone, it’s Jennifer Uhlarik again. Glad to be back with you again this month. Make sure to read to the end to find out about my surprise giveaway.

Today, I wanted to share a bit about one of the recent topics I’ve been researching—how a person became a doctor in the Old West. I would guess most people have heard of some of the abominable practices of early medical doctors. Bloodletting, purging, leeches. Or later on, the use of the toxic and ineffective combination of calomel and castor oil for various ailments. Or the Civil War surgeons who performed amputation after amputation without disinfecting anything or anesthetizing their patients. It gives me the shivers to think what sick or wounded people were subjected to in order to feel better—only to grow worse and die in many cases.

Doctors today go through many years of schooling, residency, and fellowships, and most (if not all) mortgage their future to pay for it all. But it wasn’t always that way. Back in the 1800’s, there were three methods in which a person could become a doctor.

Attend medical school.

Apprentice under a knowledgeable doctor.

Purchase a diploma from a diploma mill.

Yikes! Purchase a diploma and become a doctor? Yes. Somewhere around the early 1850’s, states began requiring credentials to practice medicine, and not long after that, diploma mills began popping up. If you could pay the fee, you could receive a diploma titled in your name, stating you were capable to practice medicine. What a frightening thought. No training. No lectures. No tests. Just pay the cash, and here’s a diploma to flash.

A more respected route was the apprenticeship. Many who wanted to learn medicine but couldn’t afford to attend medical school would choose this route. What this entailed was for the apprentice to work with a local doctor who was willing to teach him about medicine. When apprentices first started their apprenticeships, they would likely spend more time caring for the doctor’s horses than real patients. Apprentices would chop and carry wood, clean the doctor’s office, run the doctor’s non-medical errands, all to pay for his training and upkeep. He would also ride along on calls or watch procedures performed in the office. And eventually, after watching, listening, and learning, the apprentice would be given the opportunity to attempt the procedures himself.

The length of apprenticeships varied, and it depended largely on how much the doctor could teach and how quickly the apprentice learned. Once the doctor had taught all he could to his student, he would write up a document that stated the apprentice was knowledgeable in the practice of medicine and was capable of practicing on his own. The apprentice then could start his own office as a full-fledged doctor. This method of study produced many very qualified doctors in the Old West, but began to fall out of favor in the early 1870’s. I’m sure some continued to apprentice under local doctors for a bit longer, but this time frame was also when medical schools began to grow, both in number and quality.

|

© Dana Hughes

|

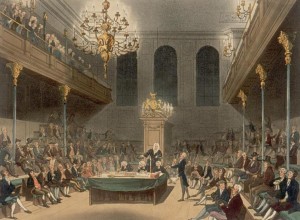

In 1850, there were approximately forty medical schools in the United States. That number swelled to more than sixty by 1876. Many of these schools were found out West, and the cost to attend was very affordable, since the residents of the western states and territories tended to be less than affluent. During this time period, students were required to attend two four-month-long sessions. These sessions would occur a year apart. Students would hear lectures on anatomy, physiology, midwifery, chemistry, and surgery, and the teachers would present some cases using cadavers obtained by grave-robbing. Anyone who could pay the money and completed both four-month sessions would be given a diploma. These newly-graduated doctors often went on to apprentice under a more established physician, but that practice began to fall out of favor by the early 1870’s.

By the turn of the century, medical schools began to improve. Prior to this point, there were few admission requirements other than to pay tuition. Shortly before 1900, medical school admission became more selective, coursework grew longer, and more hands-on practice in autopsy and dissections was given. Students were required to spend more time studying pathologies of disease. They attended conferences where strange maladies were presented. Hospitals were used for teaching on live patients with real maladies and injuries. But it wasn’t until 1910 that true standards of medical education were created, causing many of the Western medical schools to close because they couldn’t comply.

|

© Jennifer Uhlarik

|

So now it’s your turn. If you had lived during these times and wanted to be a doctor, which path would you have taken—diploma mill, apprenticeship, or medical school? Leave your email address if you would like to be entered in the drawing for two handmade soaps (Rosemary and Smashed Pumpkin Pie scents).

Thanks for visiting. See you all next month!

.jpg) Jennifer Uhlarik discovered the western genre as a pre-teen, when she swiped the only “horse” book she found on her older brother’s bookshelf. A new love was born. Across the next ten years, she devoured Louis L’Amour westerns and fell in love with the genre. In college at the University of Tampa, she began penning her own story of the Old West. Armed with a B.A. in writing, she has won the 2012 CWOW Phoenix Rattler, 2012 ACFW First Impressions, and 2013 FCWC contests, all in the historical category. She is also the winner of the 2013 Central Florida ACFW chapter's "Prompt Response" contest. In addition to writing, she has held jobs as a private business owner, a schoolteacher, a marketing director, and her favorite--full-time homemaker. Jennifer is active in American Christian Fiction Writers and lifetime member of the Florida Writers Association. She lives near Tampa, Florida, with her husband, teenaged son, and four fur children.

Jennifer Uhlarik discovered the western genre as a pre-teen, when she swiped the only “horse” book she found on her older brother’s bookshelf. A new love was born. Across the next ten years, she devoured Louis L’Amour westerns and fell in love with the genre. In college at the University of Tampa, she began penning her own story of the Old West. Armed with a B.A. in writing, she has won the 2012 CWOW Phoenix Rattler, 2012 ACFW First Impressions, and 2013 FCWC contests, all in the historical category. She is also the winner of the 2013 Central Florida ACFW chapter's "Prompt Response" contest. In addition to writing, she has held jobs as a private business owner, a schoolteacher, a marketing director, and her favorite--full-time homemaker. Jennifer is active in American Christian Fiction Writers and lifetime member of the Florida Writers Association. She lives near Tampa, Florida, with her husband, teenaged son, and four fur children.

.jpg)