by Martha Hutchens

|

| 109 E. Palace, image by Martha Hutchens |

There’s a little alley in Santa Fe which opens into a courtyard. Today, it hosts a small open-air craft fair.

But in 1943, it became the gateway to a secret city. Welcome to 109 East Palace.

Picture the men and women who arrived here, told only that their work would be crucial to the war effort. Scientists, engineers, craftsmen, and soldiers, all told to report to 109 E. Palace, Santa Fe, NM.

They arrived by private car, or by a military bus that brought them from the nearest train depot. They were tired, dusty, and thirsty. Most probably weren’t happy when they learned they had forty more miles to travel, over roads that meant it would take up to four hours.

|

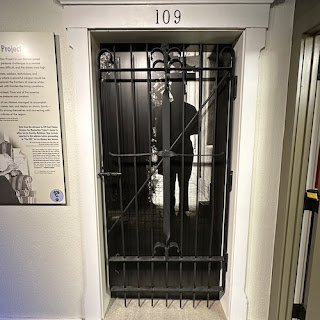

| Gate from the alley at 109 E. Palace, Currently at the Los Alamos History Museum Image by Martha Hutchens |

Their first test was simply to find the office. The alley had a fence and a gate. The building that actually opened onto East Palace was a bakery. Many stopped there to get directions. Santa Fe was a small town. Despite government secrecy, everyone knew where strangers in town probably needed to go. Someone was sure to tell them to go through the gate and to the building at the back of the courtyard.

There they met Dorothy McKibbin. She was a friendly face to people who desperately needed to see one.

Dorothy was born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri. Like many others, she traveled to New Mexico after she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. After a year, she was pronounced cured and returned to her home. She married and had a son, but her husband soon died of Hodgkin Lymphoma. Dorothy had enjoyed the climate and scenery of New Mexico, and decided to return there. She worked as a bookkeeper until the beginning of World War II, when her company decided to pursue war-related opportunities and her position was eliminated.

In March of 1943, she met Robert Oppenheimer, who offered her a job as a secretary. She accepted, not knowing what the job would entail, just like the majority of Manhattan Project workers.

She probably didn’t know what her job would entail on any given day for the rest of the war. She filled out passes that allowed newcomers to enter Los Alamos. She operated two cantankerous phone lines between her office and the lab. She babysat children and pets so that mothers could make the most of their one day of shopping a month. She guarded top secret papers, and warned newcomers that the words “Los Alamos” were classified. She knew where people on The Hill—the nickname for Los Alamos to this day—might find whatever they needed, if it could be found. Whether it was rope for a makeshift fire escape from a second floor apartment or a dentist that would make room in his roster for a last minute appointment, she could find it.

Martha Hutchens is a transplanted southerner who lives in Los Alamos, NM where she is surrounded by history so unbelievable it can only be true. She won the 2019 Golden Heart for Romance with Religious and Spiritual Elements. A former analytical chemist and retired homeschool mom, Martha is frequently found working on her latest knitting project when she isn’t writing.

Martha’s current novella is set in southeast Missouri during World War II. It is free to her newsletter subscribers. You can subscribe to my newsletter at my website, www.marthahutchens.com

After saving for years, Dot Finley's brother finally paid a down payment for his own land—only to be drafted into World War II. Now it is up to her to ensure that he doesn't lose his dream while fighting for everyone else's. No one is likely to help a sharecropper's family.

Nate Armstrong has all the land he can manage, especially if he wants any time to spend with his four-year-old daughter. Still, he can't stand by and watch the Finley family lose their dream. Especially after he learns that the banker's nephew has arranged to have their loan called.

Necessity forces them to work together. Can love grow along with crops?

Dorothy was born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri. Like many others, she traveled to New Mexico after she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. After a year, she was pronounced cured and returned to her home. She married and had a son, but her husband soon died of Hodgkin Lymphoma. Dorothy had enjoyed the climate and scenery of New Mexico, and decided to return there. She worked as a bookkeeper until the beginning of World War II, when her company decided to pursue war-related opportunities and her position was eliminated.

In March of 1943, she met Robert Oppenheimer, who offered her a job as a secretary. She accepted, not knowing what the job would entail, just like the majority of Manhattan Project workers.

She probably didn’t know what her job would entail on any given day for the rest of the war. She filled out passes that allowed newcomers to enter Los Alamos. She operated two cantankerous phone lines between her office and the lab. She babysat children and pets so that mothers could make the most of their one day of shopping a month. She guarded top secret papers, and warned newcomers that the words “Los Alamos” were classified. She knew where people on The Hill—the nickname for Los Alamos to this day—might find whatever they needed, if it could be found. Whether it was rope for a makeshift fire escape from a second floor apartment or a dentist that would make room in his roster for a last minute appointment, she could find it.

Dorothy spent a large part of her time in an office filled with boxes. Anyone from Los Alamos knew they could leave their purchases at her office. She also arranged for twice daily deliveries to The Hill. If you needed something that you couldn't find in Los Alamos (which was most everything!), a call to Dorothy would have it delivered later that day. For a large part of the project, people were only allowed to leave Los Alamos for one day in a month, so this was a lifesaver.

Dorothy hosted many weddings at her house, because churches didn’t like to have a wedding where neither the bride nor the groom could give their name.

Dorothy was called the First Lady of Los Alamos, but I think she was the laboratory’s mother hen.

The office in Santa Fe remained open until 1963. When it closed, Dorothy retired.

Today there is a plaque commemorating this unique place. It reads, “All the men and women who made the first atomic bomb passed through this portal to their secret mission at Los Alamos. Their creation in 27 months of the weapons that ended World War II was one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time.”

Dorothy was called the First Lady of Los Alamos, but I think she was the laboratory’s mother hen.

The office in Santa Fe remained open until 1963. When it closed, Dorothy retired.

|

| Plaque at 109 E. Palace Image by Martha Hutchens |

Today there is a plaque commemorating this unique place. It reads, “All the men and women who made the first atomic bomb passed through this portal to their secret mission at Los Alamos. Their creation in 27 months of the weapons that ended World War II was one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time.”

Dorothy McKibbin was a large part of this story.

Martha Hutchens is a transplanted southerner who lives in Los Alamos, NM where she is surrounded by history so unbelievable it can only be true. She won the 2019 Golden Heart for Romance with Religious and Spiritual Elements. A former analytical chemist and retired homeschool mom, Martha is frequently found working on her latest knitting project when she isn’t writing.

Martha’s current novella is set in southeast Missouri during World War II. It is free to her newsletter subscribers. You can subscribe to my newsletter at my website, www.marthahutchens.com

After saving for years, Dot Finley's brother finally paid a down payment for his own land—only to be drafted into World War II. Now it is up to her to ensure that he doesn't lose his dream while fighting for everyone else's. No one is likely to help a sharecropper's family.

Nate Armstrong has all the land he can manage, especially if he wants any time to spend with his four-year-old daughter. Still, he can't stand by and watch the Finley family lose their dream. Especially after he learns that the banker's nephew has arranged to have their loan called.

Necessity forces them to work together. Can love grow along with crops?

Hi Martha, I enjoyed reading your post. I lived in Albuquerque for 18 months when my husband was in the Air Force. I'm from SW Missouri, so I understand the change of climate in NM. We loved it there, but missed home too much to stay there. Interesting post!

ReplyDeleteThank you for continuing to post about this unique place and time in history. I immediately Google Dorothy to see how long she lived; she died in 1985 I believe. (short term memory issues, lol) I wonder if she would have talked about her unique job.

ReplyDelete