Three years ago, when I was reading/researching for Elinor, my first Lost Colony story, there was so much I still didn’t know about the subject, or all the politics surrounding the expeditions from England to the New World. One nation jockeying for position with another for control of new resources (see my original post here), opposing factions within England herself vying for position and the favor of the queen, even while war brewed with Spain. The Roanoke colonists and their plight were rather lost in the shuffle when it came to national defense and personal conflicts.

%20copy.jpeg) |

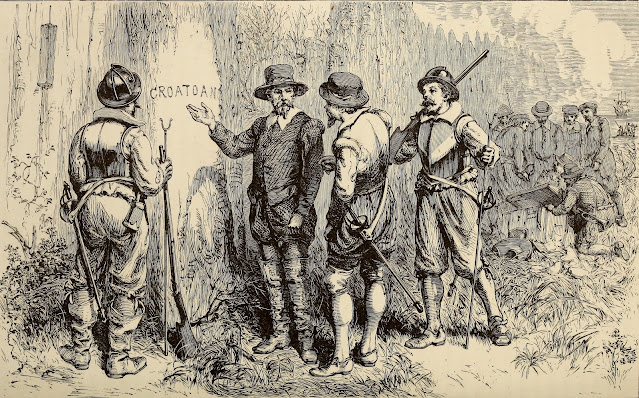

| The arrival of the Englishmen in Virginia (1590). Engraving by Theodor De Bry, from a drawing by John White |

I suppose, then, that it isn’t much of a surprise, when it comes to the question of what really happened to those colonists, theories and arguments abound.

As far as the most immediate word on what happened, we have exactly one primary source: the word (and fragment of a word) carved into a tree and a palisade post by the colonists themselves. After that is the written report by John White, professional artist turned governor of the colony, sent back to England shortly after their landing to plead on behalf of his people. Roanoke Island was never supposed to be the site of their settlement site, after all, although it isn’t quite clear what their chosen location would have been. The squabble with Simon Fernandez, navigator of the main ship that carried the colonists over, is documented, although no rational reason (in retrospect) is given for his insistence on dumping the colonists at the last-known English fort. Despite the eerie discovery of said fort to be abandoned, Fernandez did not budge on his decision. The colonists, knowing they were short on supplies and that the island had been at best a temporary hunting location for indigenous peoples, panicked and unanimously decided White should return to England to represent them.

White arrived to find his homeland at war with Spain and all the ports locked down tight. Though he managed to finagle the use of two small ships the following spring, this expedition met with disaster in the form of attack by French privateers. Wounded in battle, White returned to England once again, and not until 1590 would he be granted permission to make another attempt to go to the colonists’ aid—and then it was only the briefest of welfare checks, without supplies, additional settlers, or even a personal servant—only the luggage he could carry. Seeing to the English colony ranked low indeed in the priorities of captain and crew, and White details all their doings on the way around the Atlantic Basin.

One can sense the tension—his excitement—in the accounts as they neared what would later be called the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Glimpses of smoke, ashore. No thought of stopping off at Croatoan Island, where the famed Manteo was born (and his mother presumably still led as weroansqua), only pressing toward the last-known location of the colony: Roanoke Island.

We know by his account that they found the town site even more thoroughly abandoned than the fort of 1586. A palisade surrounded the grounds, stripped even of buildings, only the former ship’s guns and chunks of iron (for the making of shot) left behind. Two inscriptions they found, “CRO” carved on a tree and “CROATOAN” on a palisade post, which White rejoiced over because he knew perfectly well what that word referred to. Markedly absent were any crosses, the sign he’d instructed the colony to use if they’d left under duress.

|

| The Lost Colony 19th-century illustration depicting the discovery of the abandoned colony, 1590 |

His joy was short-lived, however, as a dreaded Atlantic sea storm brewed, preventing the expedition from backtracking to Croatoan Island, damaging the ships and pushing them so far off course they had no choice but limp back to England.

White was never, despite all his efforts, able to persuade anyone to carry him back across the ocean again. He never again saw his daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter, famous for being the first English child born on American soil.

Efforts were made in successive years, however, to locate the colony. It was in fact one of the directives given the Jamestown explorers and settlers, but by that time (twenty years later), word through the Native grapevine was vague at best and misleading at worst. The Spanish had also been searching, recording that they’d located a landing place, matching the description of the one White’s group used in 1590.

Captain John Smith of Jamestown reported that nothing was known of the English colonists except that men “clothed like him” lived at a particular location to the south, and that a handful of surviving prisoners were held at another location and put to forced labor “beating copper” by another Native chieftain. William Strachey, secretary of the Jamestown colony, makes the claim that Powhatan himself (the formal name of the paramount chieftain Wahunsenecawh) boasted of having slaughtered any remaining colonists.

Less than a hundred years later, however, an explorer named John Lawson reported the discovery of the Hatteras Indians, many of whom had gray or blue eyes and whose oral history stated their descent from “English” people with clothing and devices like the explorers, and who could “talk from a book.” He mentions elsewhere that the Hatteras natives also dressed in a manner reminiscent of the English, unlike other tribes.

This is the account that most often gets dismissed by those following Lost Colony lore, with Strachey’s sensationalist claim receiving the most weight. Why is that?

What really happened?

Recent expert on the Lost Colony, David Beers Quinn, puts forth an array of possibilities. People line up behind one or the other, latching on to favorite theories according to what seems the most sensible to them.

Enter Scott Dawson, Hatteras native himself, who grew up with various histories and legends passed down through grandparents and great-grands, supporting the idea that at least some of the Roanoke colonists survived by assimilating with the Croatoan people:

His book The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island is a longer account of his archaeological efforts and summary of the various theories. He cites Samuel Purchas as being the source for the claim that the Powhatan slaughtered at least some of the English colonists, but he likely drew from Strachey’s work—which, in my humble opinion, bears a definite propagandist or at least sensationalist tone. Dawson also mentions that after the death of Queen Elizabeth, there was possibly less motivation on her successor King James’s part to seek out the “lost” colonists because it would validate the New World holdings of Walter Raleigh, who King James imprisoned, accused of treason, and later had executed.

The possibility of the English colonists surviving by assimilation was long dismissed—or suppressed—by those who found it distasteful that those of “pure” English and/or European descent might have intermingled with Indigenous peoples. This seems ridiculous or even alien in our day and time, doesn’t it? Yet it was, historically speaking, an important consideration in the way the accounts and evidence were weighed and interpreted.

I’m not sure much has changed in regards to that, today. 😊

~*~*~

Blurb for VIRGINIA:

The White Doe of the Outer Banks Grows into Womanhood

Return to the “what if” questions surrounding the Lost Colony and explore the possible fate of Virginia Dare--the first English child born in the New World. What happened to her after her grandfather John White returned to England and the colony he established disappeared into the mists of time? Legends abound, but she was indeed a real girl who, if she survived to adulthood, must have also become part of the legacy that is the people of the Outer Banks. In the spring of 1602 by English reckoning, "Ginny," as she is called by family and friends, is fourteen and firmly considered a grown woman by the standards of the People. For her entire life she has watched the beautiful give-and-take of the Kurawoten and other native peoples with the English who came from across the ocean. She's enjoyed being the darling of both English and Kurawoten alike--but a stirring deep inside her will not be put to rest.

One careless decision lands her and fellow “first baby” Henry Harvie, along with their Kurawoten friend Redbud, in enemy hands. Carried away into Mangoac territory, out of the reach of Manteo and the others, she must learn who she truly is—not only the daughter of Elinor and Ananias Dare but also a child of the One True God, who gives her courage to go wherever the path of her life might lead.

AUTHOR BIO:

Thank you for posting today, and welcome if it is your first time here! This is very interesting. I can only imagine John White's distress at not being able to find his family.

ReplyDeleteThank you for responding, Connie, and for the welcome! (I've actually had the honor of posting once or twice before ...) And yes, the sheer emotion of that, as a mother and grandmother myself, really gripped me when I was writing the first book!

ReplyDelete