When I hear the word “windmill,” I picture a tall tower with a multi-blade fan sitting high above the prairie. There is also a Dutch windmill with four giant blades attached to a stout building. Now, mammoth versions generate electricity. However, not all of these structures are true windmills. The tower on the prairie is usually a wind pump, and the modern ones are wind generators. The only actual windmills operate a mill, like a grain mill.

Man has harnessed the power of wind since antiquity. Think of sailboats. Early windmills didn’t look like the ones we see today. They operated like merry-go-rounds with sails around the outside edges to propel them. Many early sails looked and functioned like the ones on boats. Wind would blow on the sails, causing the mill to turn.

The timeline for windmills throughout history is a bit fuzzy. They became more common by around 900 AD, particularly in the Middle East and Western Asia, where they were used to grind grain or pump water. Some had triangular-shaped sails like boats. Others were tall rectangles made of wood or reeds.

By the 11th century, merchants and crusaders had introduced wind technology to Europe (mainly England and the Netherlands). Around that time, the post mill was introduced. As the name suggests, blades were mounted on a tall post (or tall, slender building) that could be rotated to catch the wind. In some cases, simple cloth sails were replaced by blades constructed of a lattice frame covered with cloth. The fabric could be rolled up or let out.

As technology advanced, hollow-post mills were created. The outside of the post could turn to face the wind while the machinery in the middle didn’t rotate. By the end of the 13th century, tower mills replaced these. In a tower mill, only the cap at the top of the tower needed to rotate to turn the blades toward the wind while the rest of the structure remained stationary. The cap was manually turned using winches and gears.

The Dutch invented smock mills in the 17th century. The lower part of the tower was made of brick or stone, which could be built on wet surfaces. The upper part, typically a wooden octagon looked like a “smock” that overlapped the bottom—like a dress over legs. See the picture below.

In the Netherlands, the blades could be positioned as communication signals when the mill wasn't in use. A “+” sign meant that the mill was open for business. “X” meant closed. Other signals were designated for celebration or mourning. They were even used in World War II to warn Jews of Nazi operations.

Immigrants

brought windmills to the New World, and technology advanced. The automatic

fantail, which would turn the blades into the wind, was invented in 1745. Spring

sails appeared in 1772. These replaced lattice and fabric with giant shutters.

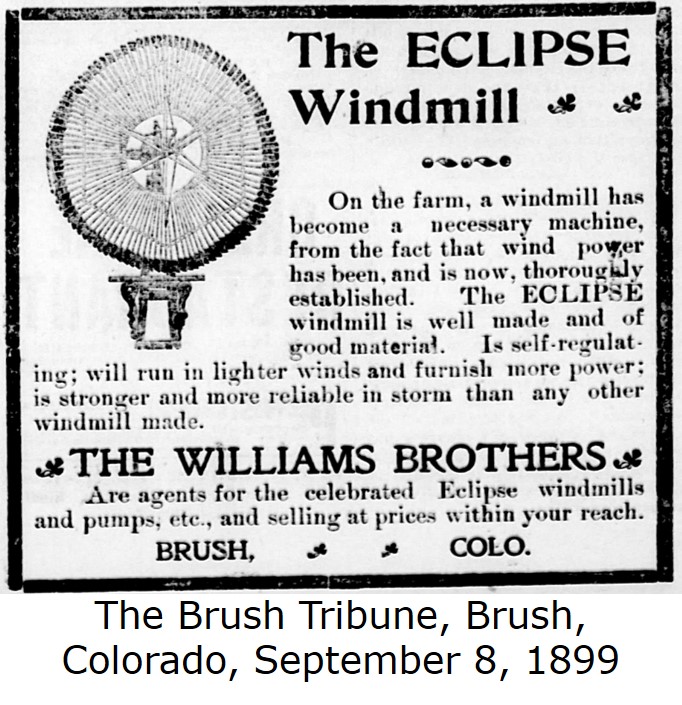

The ”American windmill,” common in the western states, was invented in 1854. These are the ones I remember from road trips I took as a child.

By the early 1900s, windmills could generate electricity. However, they fell out of favor as steam engines dominated the power industry. Over time, their use was limited to rural areas without another power source.

Now, giant

wind turbines again dot the landscape. Who would have imagined the innovation

and changes involved in getting from then to now?

***

”Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection

Four

historical romances celebrating the arts of sewing and quilting.

Mending

Sarah’s Heart by Suzanne Norquist

Rockledge,

Colorado, 1884

Sarah

seeks a quiet life as a seamstress. She doesn’t need anyone, especially her

dead husband’s partner. If only the Emporium of Fashion would stop stealing her

customers, and the local hoodlums would leave her sons alone. When she rejects

her husband’s share of the mine, his partner Jack seeks to serve her through

other means. But will his efforts only push her further away?

Thank you for posting. It was interesting to learn of the progression from the early versions to now.

ReplyDelete