By Terrie Todd

|

| The Blitz convinced many British parents to evacuate their children. |

In 1940, fearing that Nazi invasion of England was imminent, the British government devised a plan to evacuate children to the relative safety of its Dominions—Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Canada. Although numerous upper-class women and children had already fled the country to Canada and the United States (despite disapproval of both the King and Prime Minister Churchill because of the defeatist implications), many who wished to leave could not afford to. The Children’s Overseas Reception Board (CORB) was formed and tasked with running the scheme.

|

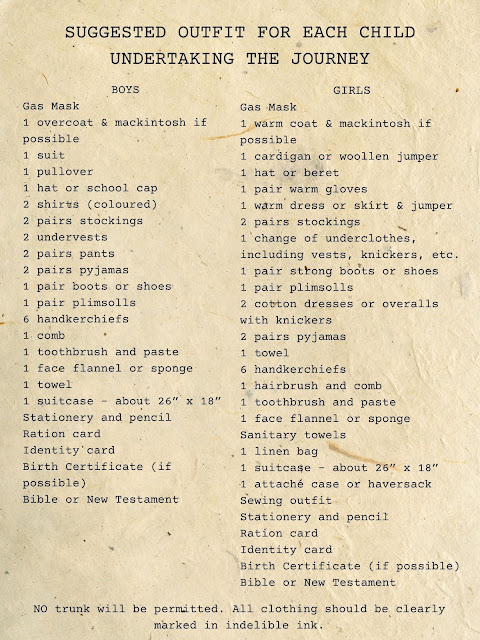

| The list sent to parents of CORB children |

A surprising number of parents wanted their children to participate. It’s a difficult thing for most of us to understand. How could anyone send their children thousands of miles away, across an ocean (infested with enemy submarines), into the hands of strangers for an undetermined amount of time? Then again, who among us has endured rationing of food, gasoline, and a host of other things? We don’t know what it’s like to hear air raid sirens, to flee to bomb shelters, to spend the night in cramped quarters with strangers. To venture out after the all-clear signal, not knowing whether we’ll still have a home or even a country. For these parents, all of that was becoming their new normal. Meanwhile, just across the channel, France had already been invaded. Horror stories were making their way to the British who felt like sitting ducks, next in line. Parents will do anything to keep their children safe. Over 211,000 applied.

One of the best books I found to research my novel.

The mind-boggling task of organizing passages, in the middle of a war, for the 25,000 children who were eventually approved, along with volunteer escorts, fell to Geoffrey Shakespeare, the Secretary for Dominions Affairs. Marjorie Maxse took charge of the welfare section of CORB and remained at the heart of the daily work until the end of the war. By September, 1,532 children had sailed to Canada (in nine parties), 577 to Australia, 202 to New Zealand, and 353 to South Africa.

Tragedy Strikes

|

| The SS City of Benares |

On September 17, 1940, just three months into the evacuation program, enemy torpedoes hit the troop ship SS City of Benares. On board were 90 children bound for homes in Canada. The ship was abandoned and sank within 30 minutes. A British destroyer picked up 105 survivors, while 42 were left adrift in a lifeboat for eight days. 77 of the CORB children died in the sinking. This unthinkable tragedy brought an end to the evacuation program.

The whole scheme had been controversial on several levels, and on both sides of the ocean. Racial, health, religious, and class issues factored in as each Dominion specified who and how many children they would accept. No one knew what the long-term effects might be of separating children from their families. Arguments abounded on both sides. What was expected to last the duration of a school term dragged into five or six years. Children who were nine when they left home returned as teenagers. Many younger children felt more closely bonded with their foster families than with the parents they barely remembered. Some returned to younger siblings they’d never met.

Among the “Guest Children” who went to Canada, experiences varied as widely as can be imagined. While some evacuees were indeed traumatized for life, others thrived—choosing to stay or return after the war. British psychiatrist Anna Freud concluded that “Love for the parents is so great that it is a far greater shock for a child to be suddenly separated from its mother than to have a house collapse on top of him.”

Note from the Queen (mother of current Queen Elizabeth), 1900-2002

Even If We Cry is Terrie’s novel about the Guest Children and is currently

being pitched to publishers. Terrie is the award-winning historical fiction author of The Silver Suitcase, Maggie’s War, Bleak Landing, Rose Among Thornes, and The Last Piece. She also writes a weekly “faith and humor” column for the Graphic Herald called Out of My Mind. In 2020, she published a collection of her favorite columns in her only nonfiction book, Out of My Mind. Terrie is represented by Mary DeMuth of Books & Such Literary Agency. She lives with her husband, Jon, on the Canadian prairies.

being pitched to publishers. Terrie is the award-winning historical fiction author of The Silver Suitcase, Maggie’s War, Bleak Landing, Rose Among Thornes, and The Last Piece. She also writes a weekly “faith and humor” column for the Graphic Herald called Out of My Mind. In 2020, she published a collection of her favorite columns in her only nonfiction book, Out of My Mind. Terrie is represented by Mary DeMuth of Books & Such Literary Agency. She lives with her husband, Jon, on the Canadian prairies. Bitter war might be raging overseas, but Rose Onishi is on track to fulfill her lifelong goal of becoming a dazzling concert pianist. When forced by her own government to leave her beloved home to work on a sugar beet farm, Rose’s dream fades to match the black soil working its way into her calloused hands.

When Rusty Thorne joins the Canadian Army, he never imagines becoming a Japanese prisoner of war. Only his rare letters from home sustain him—especially the brilliant notes from his mother’s charming helper, which the girl signs simply as “Rose.”

Follow Terrie here:

Blog

Quarterly Newsletter Sign-up

Thanks for posting this morning. What a difficult decision for these families, and yet another heartbreaking story from this unthinkable hell of a war.

ReplyDeleteThere are so many stories. Thankfully, some of the children truly did feel better off for having the experience. Living in relative safety, broadening their horizons, etc.

ReplyDeleteMy, how sad. Thank you for posting.

ReplyDelete