On this date, January 17, 1912 Robert Falcon Scott, after months of dangerous travel and loss of lives and resources, made it to the South pole.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (June 6,1868-March 29,1912) was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctica.

Scott was born the third of six children to John Edward Scott and Hannah Cuming Scott. John owned a brewery in Plymouth which provided the family with a nice living. The Scotts had a history of military service, Robert’s four uncles and his grandfather had served.

After Robert began his naval career, his father sold the brewery and lost his fortune in a bad investment, forcing Robert and his younger brother Archie to financially support their mother and two unmarried sisters. His brother died of typhoid fever in 1898, placing the whole financial responsibility on Robert.

Promotions within the Royal Navy were hard sought after and rarely available. A chance meeting with Sir Clement Markham, President of the Royal Geological Society, changed everything for him. Sir Markham mentioned the plans for a new polar expedition. Scott had been part of Ernest Shackleton’s polar expeditions to both pole regions, and was intrigued by this new plan. He saw it not only as an opportunity for promotion with a salary increase, but also for national recognition.

Sir Markham had first met Scott when he was a naval cadet and was impressed with the young man and so had followed his career. Scott persuaded Sir Markham to allow him to lead the Discovery Expedition.

From 1901-1904, the Discovery team conducted many scientific experiments and mapped out the South Pole. Scott established his base of operation at McMurdo Sound, and from there his team spread out over a large area conducting scientific experiments and plotting a future path to the Pole.

The success of the Discovery Expedition placed Scott in Edwardian Society and gave him many accolades. While at a party, he met painter, sculptor and socialite Kathleen Bruce. On September 2, 1908, they married. Their only child Peter Markham Scott was born September 9, 1909.

The next year, Scott was once again overseeing a polar expedition. The expedition was to be mostly scientific with reaching the South Pole as a secondary mission. Scott had other plans. He believed motorized transportation would be the most successful means of reaching the South Pole.

Engineer Reginald Skelton developed a caterpillar track for snow surfaces. Scott was so desperate to ensure he would reach his goal of claiming the South Pole for Britain, he added Manchurian Ponies. These horses were known for their endurance in the Siberian cold. He also spoke with Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who freely shared his expertise and encouraged Scott to add sled dogs and skis.

He sent dog expert Cecil Meares to Siberia to purchase dogsand to also negotiate for the Manchurian Ponies. Meares knew nothing about horses and returned with ponies of poor quality and not suited for the long days in the arctic cold.

His crew of experts and scientists set out on June 15, 1910 on an old converted whaler, Terra Nova. Arriving in Melborne, Australia, in October 1910, Scott received a telegram that Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen was headed to the Antarctic on a quest to reach the South Pole.

Terra Nova’s journey was fraught with mishaps, the ship almost sank in a storm, and dthen was trapped in ice for twenty days. While unloading the ship one of the motorized vehicles broke through the sea ice. The late-season arrival shortened their preparation time.

Preparatory work consisted of testing equipment and setting up caches of food and supplies as far along the route as possible so the polar team could travel lighter. Worsening weather and the poor-quality ponies forced them to place their main supply point, One Ton Depot, 35 miles north of its planned location.

He learned Armundsen was camped at the Bay of Whales 200 miles east of them. Amundsen’s base was 69 miles closer to the Pole, giving him an extra advantage. Causing Scott’s team to doubt their ability to reach the South Pole.

Scott’s team left on November 1, 1911, a caravan consisting of motorized vehicles, ponies and dogs with loaded sledges traveling at different speeds all designed to support the final group who would dash to the South Pole. The party reduced in size as each support unit reached the end of their journey and returned home to report their progress. Scott reminded the returning Surgeon-Lieutenant Atkinson of the order to take two dog-teams south to meet them at the 82 degree latitude to ensure they reached home base safely.

|

| Scott's team at the South Pole. Scott is on the far right. |

On January 4, 1912, the last two four-men units had reached the 84 latitude 34 longitude south. Scott then chose the four men who would join him on the race to the pole, while the rest returned to base.

Those five reached the Pole on January 17,1912, only to find a tent containing a letter from Amundsen dated December 18, 1911. Scott kept a daily diary and on seeing his dream shattered he wrote, “The worst has happened…All the day dreams must go…Great God! This is an awful place.”

The discouraged party began the 862 mile trek back on January 19th. Scott noted in his diary that Edgar Evans’ health was deteriorating after a fall, a second fall took his life.on February 17. With 400 more miles to travel, things did not look good. Hunger and exhaustion plagued them as they struggled back to base camp.

The Terra Nova arrived back at McMonde Sound at the beginning of February. Surgeon -Lietenent Atkinson spent time helping his team unload fresh supplies before heading out with his dog teams, delaying his departure date. Coming across Teddy Evans, from the final unit sent back, in need of urgent medical attention, the surgeon was conflicted. Evans needed his help, but the dog sleds had to be delivered to Scott’s team.

When Scott reached the 82 S. three days ahead of schedule, there were no dog sleds and the exhausted team continued on. By March 2, Lawrence Oates severe frostbite left him unable to help pull the sledges. On March 10th the temperature dropped to negative 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Oates last words to Scott as he exited their tent. “I’m just going outside and may be some time.” He walked away to his death. This left Scott and two others to continue the trek.

Scott was now suffering from frostbite. After walking another 20 miles, they set up camp on March 19, approximately 12.5 miles short of One Ton Depot. A blizzard stalled them there for nine days. While the storm raged outside the tent and supplies began to run low, the men wrote their farewell letters to family and friends. Scott’s last diary entry on March 29th “For God Sake look after our people.” He left letters for the families of the five-man team, as well as letters to a string of influential people, his mother and his wife.

He also wrote “A Message to the Public” explaining the failure of the expedition was the weather and other misfortunes. Then ending on a positive note, he lauded his team for taking the risk and doing their best. He had confidence that Britain would provide for the families of all those who died attempting this great feat.

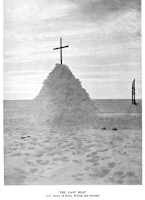

|

| Scott's team snowy tomb. |

On November 12th, 1912 the bodies of Scott and his companions were found and their records retrieved. Their final camp became their resting place. The tent roof was lowered over the bodies and a snow tomb was erected on top. A pair of skies form a rough cross. Before the Terra Nova left for home, the ship’s carpenter constructed a memorial cross on Observation Hill near the bay. it is inscribed with the names of the lost party and a line from Tennyson’s poem Ulysses. “To strive, to seek, to find, to not yield.” The cross overlooks Hut Point.

Thirty-five pounds of tree fossils were found with the remains, proving Antarctica had once been warm and connected to other continents.

The expedition’s survivors were honored with polar medals. Naval personnel received promotions. Kathleen Scott was given a widow’s benefit when posthumously Scott was granted the rank of Knight Commander of the Order of Bath.

Would you want to join a risky adventure like the Scott expedition?

Architect Angelina Du Bois took on a risky endeavor to create a town run by women where everyone is consider equal. Although the story is fiction, the heart of women during the mid-1800s is captured between the pages of Angelina’s Resolve, Book #1 of Village of Women. Available in paperback and e-book. You can find a copy online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Walmart.

Cindy Ervin Huff is an Award-winning author of Historical and Contemporary Romance. She loves infusing hope into her stories of broken people. She’s addicted to reading and chocolate. Her idea of a vacation is visiting historical sites and an ideal date with her hubby of almost fifty years would be an evening at the theater. She is agented by Cyle Young of the Hartline Literary Agency.

Thank you for posting! What a heartbreak, I can't imagine getting to the Pole and finding that note.

ReplyDelete