Into the Air Against Germany - Edited Summary of a B-17 Pilot's 20th Combat Mission, January 8, 1945

By Mary Dodge Allen

“Hey, men, the board is red, and the sky is clear. Get some sleep!”

WWII combat bomber crews stationed in East Anglia, England are on red alert to fly a bombing mission tomorrow. Before preparing for bed at 20:00 (8:00 P.M.), letters are written to mothers, wives and sweethearts back home. Idle gossip is exchanged, along with speculation about tomorrow’s target. In the background, the A.F.N. (Armed Forces Network) broadcasts the latest hit songs, such as “Rum and Coca Cola” by the Andrews Sisters.

At 02:30 (2:30 A.M.) the C.Q. (Charge of Quarters) awakens us from our fitful, nervous sleep. We wash, get dressed and then stop to eat a tasteless breakfast of soggy powdered eggs before reporting to the group briefing room. One by one, we file into the large bare room and sit as crew units on the wooden benches. Some of us engage in hushed conversation, while others fidget restlessly as they stare at the large white sheet covering the map of Europe and the combat route for today.

Promptly at 03:30 (3:30 A.M.) the briefing officer pulls back the sheet. We all focus on the end of the black tape marking the target—Frankfurt am Main. An excited buzz breaks out. “We were sure hit hard by the Luftwaffe over there last month... This ain’t no milk run brother...” All quiet down as the officer begins briefing the target M.P.I. (mean point of impact): the city railway marshalling yards, a hub connecting vital enemy areas of the Ruhr, Bavaria and Berlin. He describes the bomb–run, possible flak and fighters, radio interference, decoy planes and messages. The weatherman flashes a meteorology chart on an improvised screen. He concludes by warning us about fog at takeoff. A veteran who flew with the R.A.F. (Royal Air Force) in the Battle of Britain gives the briefing for takeoff, formation, flight altitudes and fighter escort. The C.O. (Commanding Officer) emphasizes tight defensive formation and bombs on target and wishes us happy landings.

Pilots, navigators, bombardiers and radio operators separate for specialized briefing before getting dressed for the mission. Gunners dress right away and head out to their B-17 bombers to put the fifty calibers in fighting order.

Dressing for a combat flying mission— where temperatures can reach 45 degrees below zero centigrade at 30,000 feet—requires layers of clothing, beginning with long winter underwear. Over that, I wear a khaki shirt and khaki pants (my lucky pair), and then an electrically-heated rayon suit, topped with a cotton flying suit and a wool-lined flying jacket. Wool socks are covered with electrically-heated felt slippers and wool-lined flying boots. I pull on skin-tight silk inner gloves and electrically-heated leather outer gloves, which I detest for their clumsiness. Before takeoff, I will don a wool-lined flying helmet equipped with radio earphones. I’ll also wear a parachute and harness, which has a “Mae West” water float that inflates around the chest, if necessary. I worry about working up a sweat, which can freeze at icy high altitudes.

By 04:30 (4:30 A.M.) I am driven with the rest of my crew to our B-17 G, Boeing Flying Fortress. Al, our ground crew chief from Tennessee, informs me that he’s completed preflight checks of all four engines and we’re ready to fly. (Al and his Connecticut-born assistant, Art have been up all night working on the number two engine fuel line, which gave us trouble on yesterday’s mission). I call a last-minute crew briefing, and then we pause for a quiet prayer together. My crew is ready to go.

Front row, L-R: Joe Trambley (Tail Gunner); Max Shepherd (Ball Turret Gunner); Olaf Larsen (Radio Operator); Jim Shannon (Engineer); Harold McKay (Armorer, Waist Gunner)

Back row, L-R: Lt. Gordon Dodge (Co-Pilot); Wesley Pitts (Navigator); Johnny Rosiala (Bombardier); Lt. Ralph “Lee” Minker (Pilot)

Number one engine sputters, coughs and then turns over with a steady blasting roar. We start the other three without undue trouble. They warm up as we slowly taxi out and join the line of bombers ready for takeoff. When we get a green light flash from the control tower, we roar down the long black runway and enter the air. The powerful surge and lift of a plane into flight always thrills me, for “I have slipped the surly bonds of earth…”

The bombers circle as they jockey into formation. I glance down at the patterns of land, visible through the blue haze of fog beneath us. We leave the English coast, and tension builds during the dull, tiring monotony of flight over the sinister black North Sea. I chew gum to moisten my mouth and relieve stress. Crew members take their last smokes and exchange nervous chatter on the plane interphone as we approach the enemy coast.

Number one engine sputters, coughs and then turns over with a steady blasting roar. We start the other three without undue trouble. They warm up as we slowly taxi out and join the line of bombers ready for takeoff. When we get a green light flash from the control tower, we roar down the long black runway and enter the air. The powerful surge and lift of a plane into flight always thrills me, for “I have slipped the surly bonds of earth…”

The bombers circle as they jockey into formation. I glance down at the patterns of land, visible through the blue haze of fog beneath us. We leave the English coast, and tension builds during the dull, tiring monotony of flight over the sinister black North Sea. I chew gum to moisten my mouth and relieve stress. Crew members take their last smokes and exchange nervous chatter on the plane interphone as we approach the enemy coast.

We don our oxygen masks and heavy flak helmets and jackets as we climb to a bombing altitude of 27,000 feet. A dull, penetrating cold surrounds me as I guide the bomber forward. Up ahead over the target, I see a black, hypnotizing cloud of flak explosions. It looks thick enough to walk on. The number two engine prop governor surges erratically. I can feel myself sweat.

We reach the I. P. (Initial Point) and begin the bombing run, flying straight and level with the bombardier in control. Flack explodes around us, cruel and close as we maintain a steady flight course toward the target. Ugly black bursts shake the bomber’s frame.

“We’re hit in the tail!” Joe shouts over the interphone.

“Hold steady, men!”

Johnny shouts, “Bombs Away!” Our plane surges upward at the release of the bomb weight.

“Let’s get the hell out of here!”

We turn and dive sharply. German FW 190 (Focke-Wulf) fighters attack. The loud, booming fire of our fifty-calibers breaks out. Our P-51 Mustang fighters drive the fighters away without serious damage to our plane. Our group reassembles, and I see planes missing from red squadron. Our number two engine quits, and I feather the prop. We’ll have to sweat out the flight back over the North Sea. We begin a painfully gradual descent. At 10,000 feet, I take off my oxygen mask and taste the wonderful fresh cold air as I eat a delicious frozen chocolate bar. The crew is talkative, happy. Our beautiful home base comes into view. We circle and land on the asphalt with a squeal of our tires at 15:30 (3:30 P.M.) and then taxi to our hardstand.

We are totally drained... so tired we talk in hand jerks as we unload. “Number two engine went bad again, Al. Better patch up that tail.” A G.I. truck picks us up. We drink Red Cross coffee, along with a couple of relaxing shots of Scotch, and gulp down donuts and sandwiches. Then the pilot debriefing: we hit the target, but two of our planes and their men are believed lost.

We return to the barracks and find that the damn board is red alert for another mission tomorrow.

Ralph “Lee” Minker flew 37 combat missions in the B-17 he named Blue Hen Chick, in honor of the name given to the Delaware soldiers in the American Revolution – the fightin’ “Blue Hen Chickens.” Ralph returned to the U.S. in August, 1945 at the rank of Captain. In September, he returned to Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA. He wrote this mission summary for his Winter, 1946 WWII History class. The nearly 700 letters he exchanged with his family during the war are held in The Ralph Minker/Minker Family Letters Collection at the Delaware Historical Society.

Lt. Gordon B. Dodge, Co-Pilot on Minker's crew

(Mary Dodge Allen's Uncle, who flew 35 missions and returned to the U.S. in 1945)

On February 15, 2015, Uncle Gordon, age 95, flew with us on a B-17 at a Venice, FL airshow. He met with the other riders and answered their questions about his combat missions. He said he enjoyed this flight because "nobody was shooting at me."

Note: Crew photo and photo of bombers in formation, Public Domain.

Individual photos, used with permission of the Minker and Dodge families.

Mary Dodge Allen has received two Royal Palm Literary Awards from the Florida Writer's Association. She and her husband live in Central Florida, where she has served as a volunteer with the local police department. She has worked as a Teacher, Counselor and Social Worker. Her quirky sense of humor is energized by a passion for coffee and chocolate. She's a member of Florida Writer's Association, American Christian Fiction Writers and Faith Hope and Love Christian Writers.

Mary's website: marydodgeallen.com

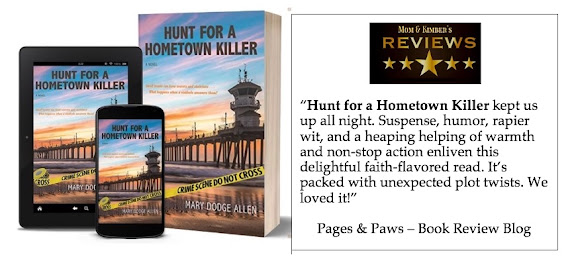

Mary's mystery/suspense novel: Hunt for a Hometown Killer is available at Amazon.com.

Thanks for posting this morning! I appreciated the bird's eye view you gave us.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you enjoyed it. I am amazed at the courage and stamina the flight crews had. It's important to remember what they went through.

DeleteI really enjoyed it. In a few words it covered the essence of the run as well as the emotions. Thanks for sharing

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you enjoyed it. This was especially poignant to me, since my Uncle Gordon flew as Ralph's co-pilot.

ReplyDelete