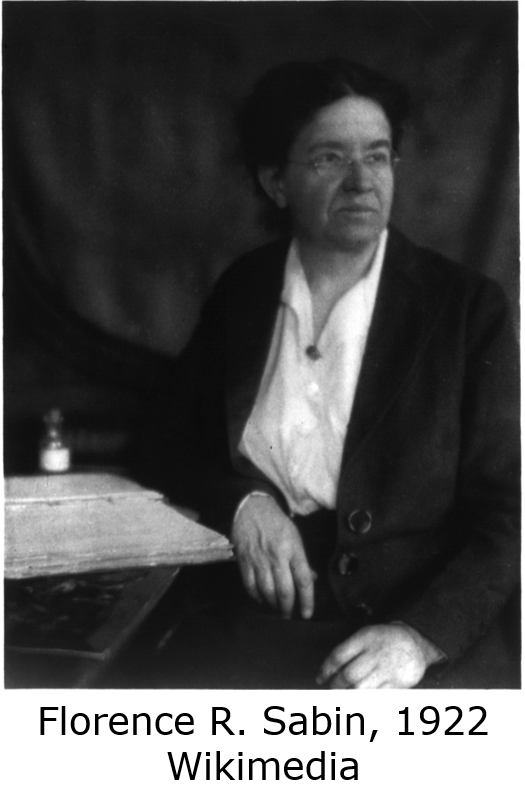

By Suzanne

Norquist

“I’ll have

the little old lady on my side.”

That’s what Colorado

Governor John Vivian said of Dr. Florence Sabin in 1946. At age 75, she championed

the overhaul of the state public health system. This, after a distinguished

career as a professor and medical researcher. Her biography frequently includes

the phrase, “She was the first woman to….”

As I studied her list of accomplishments, I didn’t even understand what most of the terms meant. But as I read her story, one thing stood out; in the face of obstacles, she focused on what she could do and didn’t let the things she couldn’t do get her down.

“I

hope my studies may be an encouragement to other women, especially to young

women, to devote their lives to the larger interests of the mind. It matters

little whether men or women have more brains; all we women need to do to exert

our proper influence is just to use all the brains we have.” – Florence Sabin

The youngest

of two girls, she was born in Central City, Colorado, in 1871 to a school

teacher mother and a mining engineer father. The family lived in a primitive

home on the side of a steep hill.

When she was seven years old, her mother died, and her father sent the girls to boarding school in Denver. Then they went to Chicago to live with an uncle and later to Vermont to live with grandparents. Despite all the moves, both girls received a good education.

In high school, Florence hoped to become a professional pianist, but a classmate bluntly informed her she was merely average. So, instead, she turned her attention to math and science—focusing on her strengths.

Florence

attended Smith College, one of the few that admitted women. She considered

herself homely with frizzy hair and squinty eyes, so she worked toward a career

rather than finding a husband. While I have my opinions about her assessment,

this is another example of focusing on her strengths.

While she was in college, her father’s health failed, and his mining ventures floundered. He wasn’t able to pay for her to complete her education. So, she took a job teaching and saved the money herself.

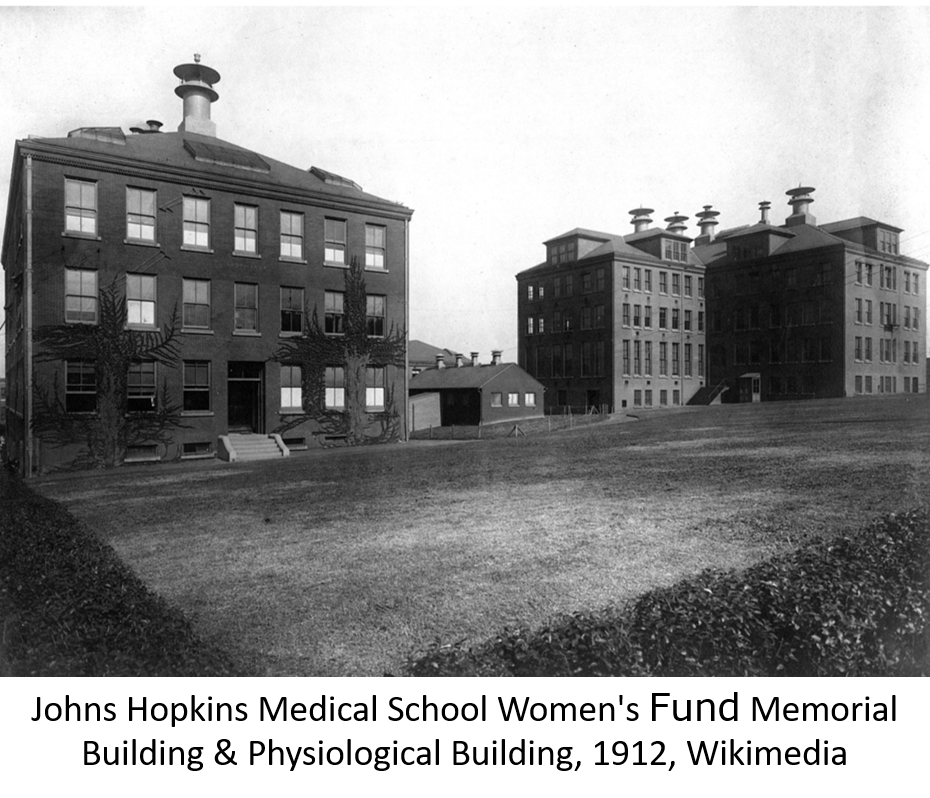

Upon receiving her degree, Florence was accepted at Johns Hopkins University Medical school. One of it's major donors required it to accept women. There she flourished and earned the respect of anatomist

Franklin P. Mall, who would be her mentor in the early part of her career.

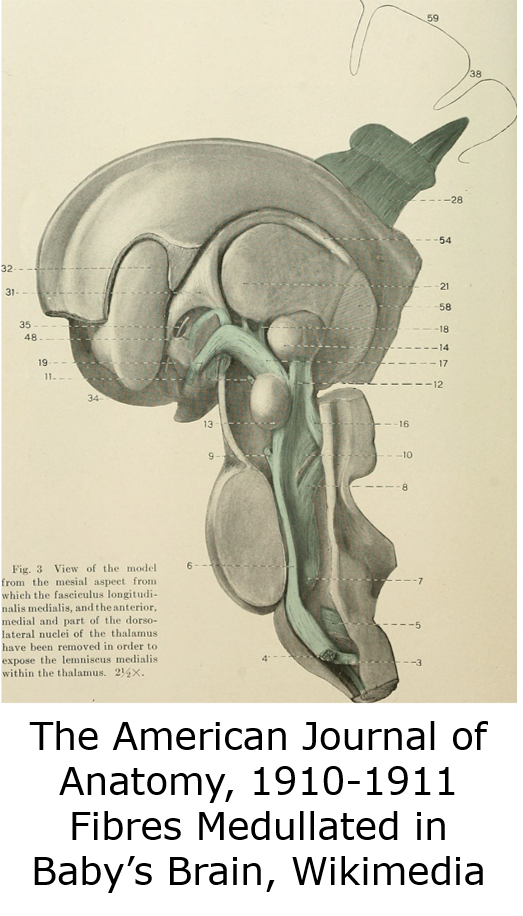

In groundbreaking research, she produced a three-dimensional model of a newborn baby’s brain stem and studied the lymphatic system.

Florence earned the credentials to be a physician, but she preferred the quiet lab to the actual doctoring. Again, playing to her strengths, she pursued medical research.

Upon

graduation, she wanted to join the faculty at Johns Hopkins. However, they didn’t

employ women professors. That didn’t stop her research. A group that supported

women’s research sponsored a fellowship for her to continue her work, and she

proved herself a competent scientist. Three years later, in 1903, she became

the first woman faculty member at Johns Hopkins University.

Her mentor passed away, sixteen years later, and many expected her to replace him as department chair. Instead, they hired a man. When her friends urged her to quit, she replied, “I'll stay, of course. I have research in progress."

They did make

her a full professor—another first for a woman.

In 1925,

she became head of the

Department of Cellular Studies at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical

Research. She retired from there in 1938.

Not surprisingly, her first retirement didn't end her career. She moved back to Colorado to be with her sister. There, the governor asked her to chair a subcommittee on health. One source said he had been criticized for not having any women leading his committees, and he hoped this old woman wouldn't cause him any problems.

At age seventy-five,

she championed the overhaul of the Colorado public health system, crisscrossing

the state to educate people and proposing sweeping legislation. The governor referred

to her as an "atom bomb" and a "dynamo."

She finally

retired when she was seventy-nine. In 1953, she passed away at age eight-one.

I can't even

begin to list her accomplishments in this short blog. There are so many. However,

I can learn from her as a person. She played to her strengths and didn't worry

about the rest.

***

Four historical romances celebrating the arts of sewing and quilting.

Mending

Sarah’s Heart by Suzanne Norquist

Rockledge,

Colorado, 1884

Sarah

seeks a quiet life as a seamstress. She doesn’t need anyone, especially her

dead husband’s partner. If only the Emporium of Fashion would stop stealing her

customers, and the local hoodlums would leave her sons alone. When she rejects

her husband’s share of the mine, his partner Jack seeks to serve her through

other means. But will his efforts only push her further away?

For

a Free Preview, click here: http://a.co/1ZtSRkK

She authors a

blog entitled, Ponderings of a BBQ Ph.D.

Thank you for posting this. What a wonderful example of perseverance!! "Play to your strengths" is a worthy life goal.

ReplyDeleteIndeed it is.

Delete