By Suzanne

Norquist

For

centuries, hotels and coaching inns provided places for weary travelers to lay

their heads. Accommodations varied from shared beds to opulent suites,

depending on how much a person was willing to spend.

With the

invention of the railroad and its westward expansion, an ordinary citizen could

travel across the country, staying at hotels along the tracks. These

centralized facilities worked because everyone took the same route with the

same stops.

That all

changed in the 1910s with the mass production of the automobile. Families could

drive wherever the road took them and spend the night in any old place.

In the early days, many travelers considered themselves explorers. They brought their own tents and equipment and set up camp along the side of the road. Few concerned themselves with staying in a farmer’s fields or people’s yards.

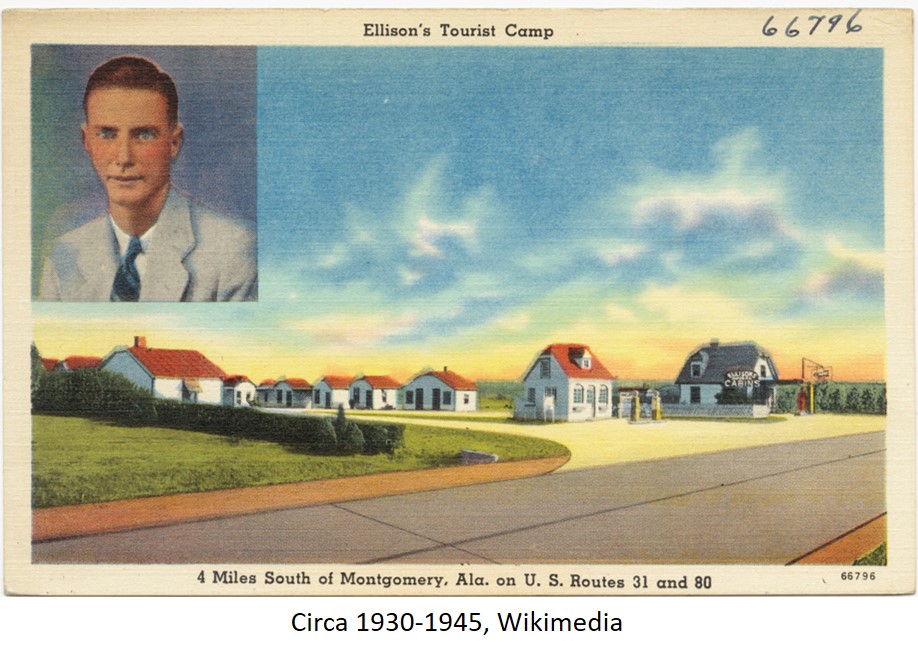

Tourist Camps (also known as auto-parks) sprouted up to solve this problem. At first, they didn’t provide much in the way of amenities, just a place to park and pitch a tent without a landowner complaining. Cities or other municipalities frequently provided the space, and often for free. By 1922, more than 1000 automobile tourist camps had sprung up along the United States byways.

By the

mid-1920s, most municipalities charged to use the camps. A fee kept the tourist

camps from becoming a place for tramps to live. It also helped to cover the

cost of trash cans and well water.

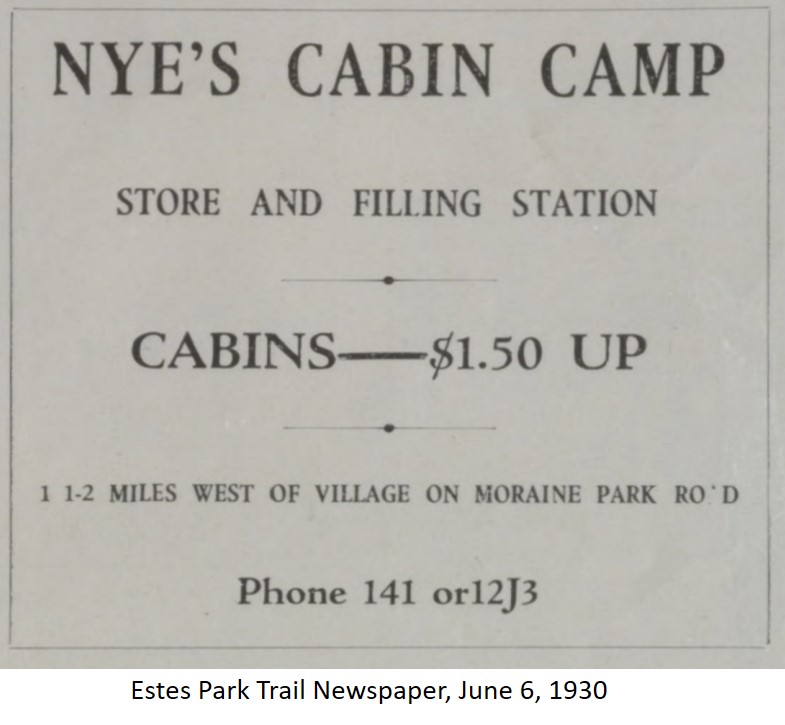

Over time, a

market for private camps with more amenities appeared. Well water with a spigot

became bathrooms with sinks and toilets. Gas stations or food vendors set up

near the camps in some places.

By the early 1930s cabin camps (aka cottage camps) began replacing tourist camps. Often, the cabins were arranged in a U-shape with a parking area in the center.

Camps ranged from simple to luxurious.

An article in the Oak Creek Times and the Yampa Leader, Oak Creek, Colorado, August 15, 1929, describes the improvements to cabin camps as follows:

“Spotless

linens and shining pots, pans, and tableware await the travelers. A commissary

is frequently nearby. Some cabin camps offer private garages and even a kennel

for the dog. All of these accommodations are usually obtainable at nominal

prices.”

In the book The

Motel in America, the authors illustrate the typical visit to a “cabin

camp”:

“At

the U-Smile Cabin Camp…arriving guests signed the registry and then paid their

money. A cabin without a mattress rented for one dollar; a mattress for two

people cost an extra twenty-five cents, and blankets, sheets, and pillows

another fifty cents. The manager rode the running boards to show guests to

their cabins. Each guest was given a bucket of water from an outside hydrant,

along with a scuttle of firewood in the winter.”

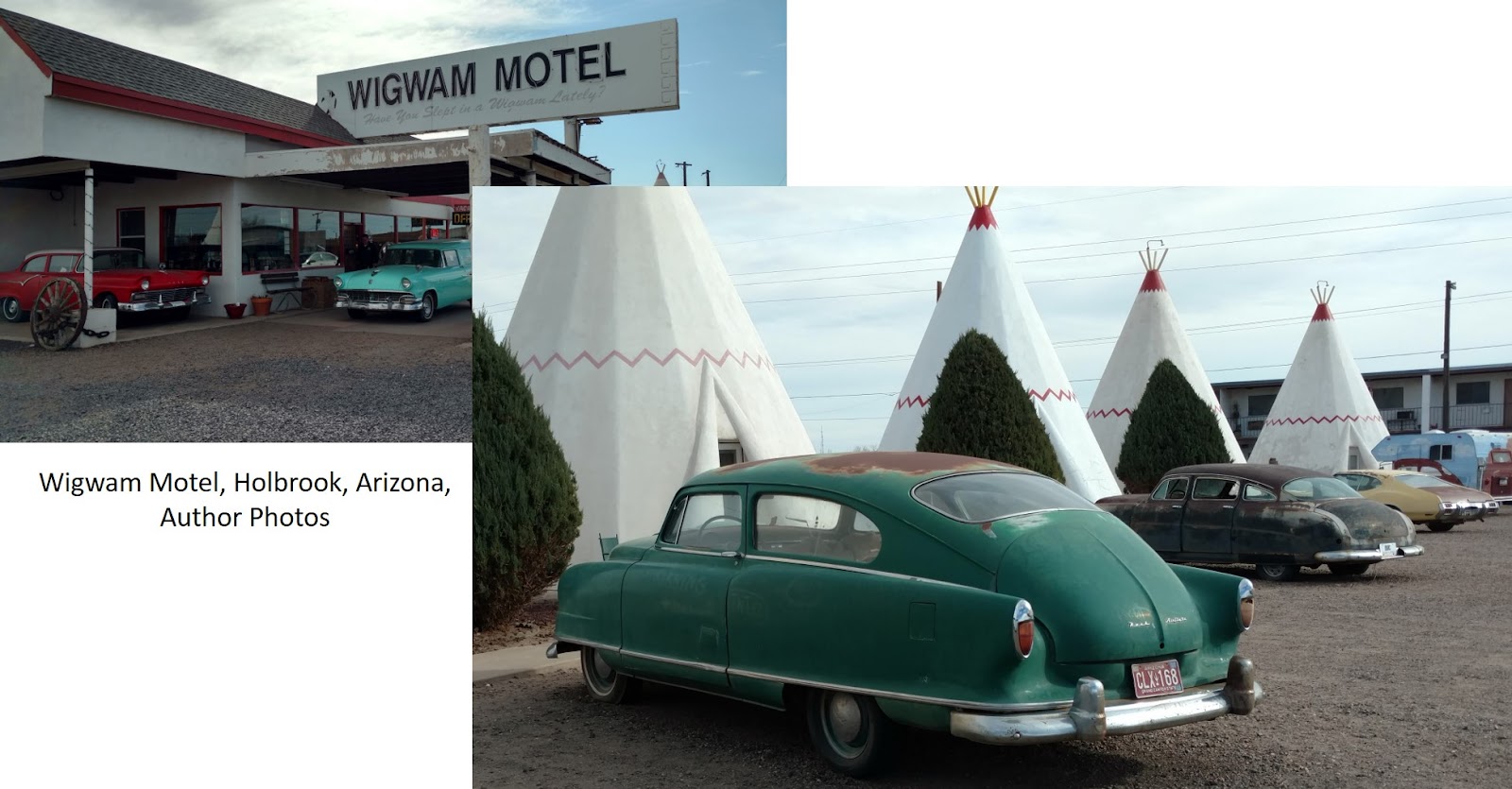

The Wigwam

Motel is a fun example of a cabin camp that still operates today. The uniquely

designed cabins draw visitors.

Eventually, property owners decided to put all the “cabins” under one roof, creating motor courts or hotels. The term “motel” is a combination of two words “mot” is from motor, and “tel” is from hotel. It was first used in 1925 when the builder of a motor hotel in San Luis Obispo, California, couldn’t fit “Milestone Motor Hotel” on the rooftop.

It took over ten years for the new term to catch on. I found a newspaper article from 1937 describing the word “motel.” The writer thought it sounded more dignified than cabin camp.

Most of these

early motels, tourist cabins, and tourist camps were mom-and-pop operations.

They provided a unique experience in American history.

At some

point, people wished for the security of an interior door instead of each room

opening to the outside. The change turns motels into the hotels of old.

From hotel to

motel to hotel with numerous travel experiences in between.

”Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection

Four

historical romances celebrating the arts of sewing and quilting.

Mending

Sarah’s Heart by Suzanne Norquist

Rockledge,

Colorado, 1884

Sarah

seeks a quiet life as a seamstress. She doesn’t need anyone, especially her

dead husband’s partner. If only the Emporium of Fashion would stop stealing her

customers, and the local hoodlums would leave her sons alone. When she rejects

her husband’s share of the mine, his partner Jack seeks to serve her through

other means. But will his efforts only push her further away?

Thank you for posting today. I still love finding that gem of accomodation that is run by "Mom and Pop". They are so much better, usually, than a chain franchise.

ReplyDeleteThey really are.

DeleteThis is an interesting post, Suzanne. Here in the Ozarks, there are lots of little cabins in the small towns. Some have been restored, some were left to deteriorate. All are very interesting and so now I know the story. Thank you!

Delete