By Jennifer Uhlarik

Yesterday, I had to do something that I don’t do very often anymore. I had to set my alarm clock. This used to be a usual part of my day. Set the clock so I could wake at the proper time to get to work…or later, to make sure my young son got off to school on time. Or my husband’s alarm would wake me when he had to get up for work. But since my husband retired and I work from home…and my son is an adult, weeks from getting married, and just moved into his own apartment, I am in that delightful stage of life where I don’t have to turn on an alarm clock except on very rare occasions. I’m loving the stage of being able to gently awaken at whatever time my body says its ready.

Have you ever thought about how people awakened in the times before alarm clocks were so readily available. I recall reading in Louis L’Amour novels how the cowboys would drink copious amounts of water before heading to their bedrolls so that their full bladders would awaken them. While that method would work to make sure you awakened at some point, it doesn’t seem a very reliable way to make sure you awakened at the right time.

So what was the answer to awakening for work on time? In places like Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, and some other countries, the answer was to hire a Knocker-Upper. Yes, there were people who could be hired to be your professional alarm clock.

|

| Granny Cousins worked as a knocker-upper from 1901-1918 |

This occupation became necessary as the Industrial Revolution began in the 1800s. As advancements in industrialization took place, Britain and other countries moved from working the family farm to people working in big cities for employers. No longer could they rise with the sun to work their fields. They had actual shifts they must work, and they needed to be sure to be awake and at their posts in timely manners. Since alarm clocks were not easily available—and often not accurate if one could purchase one—the workforce of the Industrial Revolution relied on the Knocker-Uppers.

These people were typically night owls who were awake in those dusk to dawn hours anyway and who would sleep during daylight hours until about 4 pm. Sometimes, they were elderly gentlemen. Other times, young women in the family way would fulfill the role. Still other were police officers who patrolled in those overnight hours and wanted to supplement their income with a bit extra. Whoever they were, these human alarm clocks had the sole task of being sure their clients received a gentle nudge when their wake-up time rolled around—all for about six pence a week.

Mrs. Bowers and her dog Jack

Note the rubber mallet she used to knock on

doors or windows.

However, it wasn’t as simple as going to the door and knocking or ringing the bell. To do so would awaken the household—but usually only one in the household had paid for the service. So as a knocker-upper, you didn’t want to inadvertently wake people for free. To combat that problem, these service providers developed ingenious ways of waking only the ones who had asked for a wake-up call.

Many Knocker-Uppers carried long sticks, often made of bamboo, which could reach from the street level to a second-story window. They would use the stick to tap gently on a certain window three or four times before they moved on. Others used a wood or metal baton—short in length—to tap on a door. Some chose a rubber mallet as their knocker of choice. And a few ingenious sorts used reeds or rubber tubes to shoot pebbles or peas at the window of their customer.

|

| Mary Smith used a pea shooter to awaken her customers |

Some knocker-uppers would take their jobs so seriously, they would stand and continue to knock at their customer’s door or window until the person waved to them to say they were awake. However, many were busy enough with customers that they gave three quick taps at a window or door and moved on, trusting their customer to have heard.

To make the job easier for the knocker-uppers, some customers began putting slates outside their doors with the details of when they wished to be awakened. These “knocky-boards” would often have their shifts for the week written on them, or just a general time to awaken them each morning.

|

| A customer waves to her knocker-upper to say she was awake. |

This little-known profession was well-known enough in the late 1800s that it was written about in both fiction and historical accounts. For instance, Charles Dickens included a mention of a character being in a sour mood after being “knocked up” in chapter six of Great Expectations. And in the writing on Jack the Ripper, the man who found the Ripper’s first victim, Mary Nichols, said he told a police officer in the area, but said officer was busy enough awakening people that he was non-committal about coming to investigate the body of the dead woman.

All told, this interesting profession was started during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s, and it was largely phased out in the 1940s and 1950s in most places. But in some small communities, it continued well into the 1970s.

It’s Your Turn: Have you ever heard of a knocker-upper? If you lived during the Industrial Revolution, would you have considered going into such a profession? Why or why not?

Award-winning, best-selling novelist Jennifer Uhlarik has loved the western genre since she read her first Louis L’Amour novel. She penned her first western while earning a writing degree from University of Tampa. Jennifer lives near Tampa with her husband, son, and furbabies. www.jenniferuhlarik.com

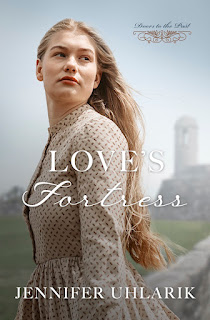

Love’s Fortress by Jennifer Uhlarik

A Friendship From the Past Brings Closure to Dani’s Fractured Family

When Dani Sango’s art forger father passes away, Dani inherits his home. There, she finds a book of Native American drawings, which leads her to seek museum curator Brad Osgood’s help to decipher the ledger art. Why would her father have this book? Is it another forgery?

Brad Osgood longs to provide his four-year-old niece, Brynn, the safe home she desperately deserves. The last thing he needs is more drama, especially from a forger’s daughter. But when the two meet “accidentally” at St. Augustine’s 350-year-old Spanish fort, he can’t refuse the intriguing woman.

Broken Bow is among seventy-three Plains Indians transported to Florida in 1875 for incarceration at ancient Fort Marion. Sally Jo Harris and Luke Worthing dream of serving on a foreign mission field, but when the Indians reach St. Augustine, God changes their plans. However, when Sally Jo’s friendship with Broken Bow leads to false accusations, it could cost them their lives.

Can Dani discover how Broken Bow and Sally Jo’s story ends and how it impacted her father’s life?

Thank you for this interesting post. I had heard about this occupation a few years ago, and joked with my grandson that it would be a perfect profession for me! I often called him in the morning to make sure he had made it out of bed in time for the bus.

ReplyDelete