By Suzanne

Norquist

The world as

we know it today wouldn’t exist without conveyor belts. We see them at grocery

stores and airports. People even ride on some of them, like moving walkways and

escalators. More importantly, they facilitate the movement of goods behind the

scenes—in factories, farms, mines, and ships—in the supply chain for everything

we buy.

How did this humble servant of humanity come to be?

Before

conveyor belts, there were elevators. As far back as the Roman Empire, people

used elevators to move themselves, animals, and materials. The Roman Colosseum

had twenty-five elevators. Six hundred pounds could be lifted in one powered by

eight men.

The Romans also had bucket elevators used to collect water. Containers mounted on a wheel or chain would lift water or other materials.

In the 17th century, elevators were installed in the palace buildings in England and France. Louis XV of France called one a “flying chair.”

Elevators are

used for batch processing, as opposed to conveyor belts, which are used for

continuous processing. For example, if our luggage arrives at the airport in

big carts, one cart at a time, that is a batch process. Instead, we watch for

our bag to come down the belt in the continuous stream of luggage.

It is unclear

when the first conveyor belts appeared, as they weren’t really a technological

breakthrough. In the 1700s, hand-operated wood-and-leather belts were used predominantly by farmers to move grain or at the docks to load

ships.

In 1790,

Oliver Evans built the first completely automated grain mill. It incorporated

conveyor belts, bucket elevators, and several other handy inventions.

Unfortunately, he struggled to sell his process to other mills. It didn’t help that he wasn’t well-liked. A Philadelphia merchant even called him a “pompous blockhead.” He went on to build steam engines and even invented an amphibious vehicle. But I digress.

Even though Oliver Evans worked with conveyor belts and steam engines, I couldn’t find evidence that he had combined the two.

The British

Navy is credited with the first recorded use of a steam-powered conveyor belt

in 1804. It streamlined the baking of biscuits for hungry sailors. Many

bakeries adopted this technology early on.

Vulcanized

rubber, invented by Charles Goodyear in 1844, allowed for sturdier, more

heat-resistant belts.

In 1892, Tom

Robins invented the first heavy-duty belts. As a conveyor belt salesman, he

tried to sell a regular belt to Thomas Edison’s ore-milling company, which

needed a sturdier product. When Robins’s employer refused to create a special

belt, Robins designed one with a competitor’s company. Robins was fired.

However, his belt won the grand prize at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and first prizes at the Pan-American Exposition and Saint Louis Exposition. He started the Robins Conveying Belt Company, which still exists today under the name ThyssenKrupp Robins.

In 1901,

Sandvik AB, a Swedish engineering company, invented steel conveyor belts. These

became the standard in the food industry.

Conveyor

belts reached full acceptance when Henry Ford used them for his assembly line

in 1913. By 1919, they were the industry standard in auto manufacturing.

Without

conveyor belts, I doubt the Industrial Revolution could have happened. Our

world would look a lot different. Something to remember the next time your suitcase

crashes down the luggage carousel at the airport.

***

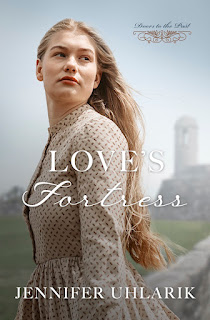

”Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection

Four

historical romances celebrating the arts of sewing and quilting.

Mending

Sarah’s Heart by Suzanne Norquist

Rockledge,

Colorado, 1884

Sarah seeks a quiet life as a seamstress. She doesn’t need anyone, especially her dead husband’s partner. If only the Emporium of Fashion would stop stealing her customers, and the local hoodlums would leave her sons alone. When she rejects her husband’s share of the mine, his partner Jack seeks to serve her through other means. But will his efforts only push her further away?

Suzanne Norquist is the author of two novellas, “A Song for Rose” in A Bouquet of Brides Collection and “Mending Sarah’s Heart” in the Thimbles and Threads Collection. Everything fascinates her. She has worked as a chemist, professor, financial analyst, and even earned a doctorate in economics. Research feeds her curiosity, and she shares the adventure with her readers. She lives in New Mexico with her mining engineer husband and has two grown children. When not writing, she explores the mountains, hikes, and attends kickboxing class.