By Jennifer Uhlarik

Most everyone is aware of Mt. Rushmore, the South Dakota monument memorializing four American presidents—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt—on the face of a granite mountainside. But do you know the history—and controversy—of this monument?

|

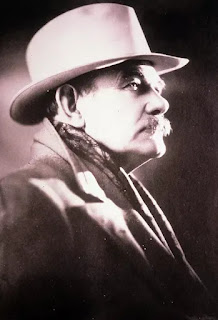

| Doane Robinson |

It was in August of 1924 when a historian from South Dakota, Doane Robinson, came up with the concept of a large stone monument to bring attention of tourists to his state. His initial concept was to memorialize western heroes such as Red Cloud, Lewis & Clark, and Buffalo Bill Cody. To accomplish this monumental goal, he contacted Gutzon Borglum, who had been working on carving the face of Robert E. Lee at Stone Mountain, Georgia, at the time. Borglum came to South Dakota twice to discuss the project, first in 1924, when he initially agreed to the project, and again in 1925, when he searched out which mountain he would carve. Upon finding Mt. Rushmore, he convinced Robinson that the faces of western heroes were too limiting—if he hoped to draw national attention, he needed to memorialize national figures. American Presidents.

The son of Danish immigrants, Borglum had little formal training in his early life, but eventually was placed in a private school in Kansas where he received some initial exposure to art. As an adult, he went to Paris where he studied at the Julien Academy and other prestigious schools. He lived for several years in various European countries and gained small amounts of success. But it was after he returned to the United States that his career truly began to take off. His artwork appeared on the Gettysburg Battlefield, in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in the Cathedral of St. John the Devine in New York among other places. But it was his large bust of President Abraham Lincoln, carved from a block of marble and put on display in a New York shop window, that ultimately led to his work on Stone Mountain, and later Mt. Rushmore.

|

| Gutzon Borglum |

Construction on the famed Mt. Rushmore began on October 4, 1927. The first face to be carved was George Washington’s, and Borglum roughed in a simple egg shape to begin with, eventually adding his detailed features later. Washington’s face was completed in 1934, seven years after it was begun. During that time, work was also begun on Thomas Jefferson’s face, situated to the right of Washington, but two years into the process, his visage was badly cracked, so the rock face had to be blown off with dynamite and started again to the left of Washington. His sculpture was completed in 1936. One year later in 1937, Lincoln’s portion was completed, and the final face—Teddy Roosevelt’s—was finished in 1939. Borglum had intended to add a carving of the early history of the United States to the monument, but he died on March 6, 1941, leaving his son Lincoln to assume the remainder of the project. But as World War 2 was ramping up, the United States decided the money allotted for Mt. Rushmore’s completion was better spent elsewhere, so the project was deemed complete on October 31, 1941.

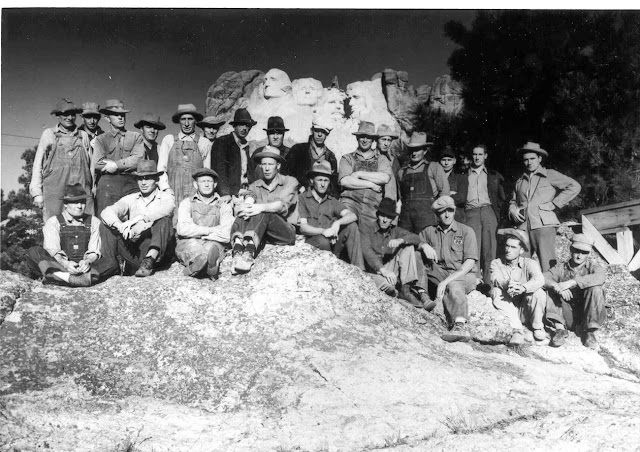

During all the years of carving, nearly four hundred men and women worked on the Mt. Rushmore project in capacities from the blacksmiths who created the tools used in the process, to winch operators who lowered workers down the rock face, to the skilled men who blasted the rock face with dynamite. Nearly ninety percent of the project was completed by blasting with explosives, which got the rough features of each president within three to five inches of the finished carving. The rest was done with small jackhammers in “honeycomb fashion”—where small holes were drilled into the rock, often close enough together that the pieces of rock would just fall away, and the faces could be buffed smooth. All told, over 800 million pounds of rock were removed to create the faces of the memorial, and according to the National Park Service website and the Smithsonian, there were no known fatalities of any work crew members during the monument’s fourteen-year creation.

|

| The final work crew to work on Mt. Rushmore in 1941, with the monument in the background. |

THE CONTROVERSY

Of course, in any venture, you can’t please all the people all the time, and Mt. Rushmore is no different. From the start, environmentalists opposed the idea of blasting away the natural beauty of a mountain to memorialize men. Ultimately, Robinson and Borglum won out, and the project went forward, despite this criticism.

Worse, the Native Americans took great issue with the project. The United States government had given The Black Hills to the Lakota Sioux as part of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, but in the 1870s, gold was found in this area, and settlers flooded the area in search of wealth. War ensued, and by the later 1870s, the government took back what had been willingly given only a decade before. So to not only lose their ancestral land, but then to have four white men’s faces blasted into the rock face was a great afront. In the 1930s, during the carving of the monument, Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear contacted Borglum by letter, requesting that the face of Crazy Horse be added among the American Presidents, but Borglum never responded. Chief Standing Bear later contacted another artist to create a separate monument, which I’ll discuss next month.

To counter the largely white perspective of Mt. Rushmore, the first Native American superintendent, Gerard Baker, who served between 2004 and 2010, encouraged park rangers to include the Lakota point of view in their tours, presentations, and in answering visitor’s questions.

It’s Your Turn: Have you ever visited Mt. Rushmore? If yes, tell us what you enjoyed (or didn’t enjoy) about the memorial. If no, would you like to—why or why not?

Award-winning, best-selling novelist Jennifer Uhlarik has loved the western genre since she read her first Louis L’Amour novel. She penned her first western while earning a writing degree from University of Tampa. Jennifer lives near Tampa with her husband, son, and furbabies. www.jenniferuhlarik.com

Love’s Fortress by Jennifer Uhlarik

A Friendship From the Past Brings Closure to Dani’s Fractured Family

When Dani Sango’s art forger father passes away, Dani inherits his home. There, she finds a book of Native American drawings, which leads her to seek museum curator Brad Osgood’s help to decipher the ledger art. Why would her father have this book? Is it another forgery?

Brad Osgood longs to provide his four-year-old niece, Brynn, the safe home she desperately deserves. The last thing he needs is more drama, especially from a forger’s daughter. But when the two meet “accidentally” at St. Augustine’s 350-year-old Spanish fort, he can’t refuse the intriguing woman.

Broken Bow is among seventy-three Plains Indians transported to Florida in 1875 for incarceration at ancient Fort Marion. Sally Jo Harris and Luke Worthing dream of serving on a foreign mission field, but when the Indians reach St. Augustine, God changes their plans. However, when Sally Jo’s friendship with Broken Bow leads to false accusations, it could cost them their lives.

Can Dani discover how Broken Bow and Sally Jo’s story ends and how it impacted her father’s life?

Jen, you always share interesting posts. I recall hearing a bit of this. I'd forgooten most of it. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your post today. What a massive undertaking!

ReplyDelete