Throughout American history, women, along with their husbands and families, have forged their way across the continent, over raging rivers and through vast woods, across blustery prairies and beneath scorching desert winds. Yet, seldom did they decide to embark on such journeys alone. That drive and desire belongs only to those courageous women who longed for a different future and to discover what the unknown world might offer them as individuals.

Such was the character and fortitude of Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh. First-born of a wealthy and well-educated but humble Quaker, John Haddon of London, and educated in England herself, Elizabeth grew up nurturing a dream of coming to the wilds of America, planted by her father who, in 1698, purchased 500 acres from a Society Friend in the wilderness of what was termed “West Jersey”. Though he never came to view his property himself, Elizabeth became absorbed, even as a child, with the desire to settle in the new country she heard so much of from her Quaker community and those who went there carrying the Gospel.

Legend has it that her father, who made his living as a blacksmith by trade but who had preached and attracted some attention while in London, later had William Penn as a guest at his dinner table. Although Elizabeth would have been too young to join the conversation, being only about fourteen at the time, something in the discourse or conversation that followed must have enticed her even more with thoughts of what the new land had to offer.

|

| English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, early Quaker and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania (1644-1718) 18th Century illustration, Wikipedia Commons |

At seventeen, Elizabeth joined the Quaker sect, and with energy and a practical mind began to set her thoughts toward America with greater earnest. However, her father, for business reasons, determined to remain in England.

Elizabeth was disappointed, ardently desiring to join the Quakers who had gone to reach the Indians, to find prosperity and freedom in this great land, and to join in their labors with them. When her father then offered the land tract to any relative who would settle it on his behalf, she pressed her own suit to go pioneering in the far-off wilderness in his stead. Sympathizing with what she convinced him was her calling, he finally gave way.

In the spring of 1700, when she was about twenty-one years of age, Elizabeth boarded a two-masted ship on the Thames. She was accompanied by a poor widow known for her good sense and discretion as her housekeeper, and two trustworthy men-servants of the Society of Friends. Weeks later, they landed in the hamlet of Philadelphia.

The Haddon land tract lay in an almost unbroken wilderness, where almost nine miles of rivers and dense forest separated the diminutive port city from the place her future home lay. To someone less brave (and perhaps youthful) the prospects of forging her way there and then taming this land might have appeared doleful. But to Elizabeth, even after enduring the travails of an ocean voyage and seeing the largeness of the task before her, she was no less purposeful and determined. She fully accepted the loneliness and inconveniences she must overcome to forge a new home and settlement in such circumstances.

Always too busy to spend time complaining, and daily trusting in her Heavenly Father’s hand, she became known for her graciousness, efficiency, and tirelessness. The Indians in the region trusted her to be truthful, just, and kind, and she, in turn, learned about natural medicines from them. Elizabeth eventually used her knowledge to aid men, women, and children for miles around. In the meantime, wherever she went, she gathered information on ways she might improve her farm, whether it was for better seeding of crops or increasing dairy production. In the meantime, her home became a universal layover for Friends traveling to the Quaker meeting house in Newtown and as a respite for other weary travelers who found themselves at her door.

Such is how she became more thoroughly acquainted with a minister by the name of John Estaugh. With several other Friends, his sleigh approached her home on a brisk winter’s evening. She had met Mr. Estaugh once before, years earlier in London when he preached there, and she was still a child. Now here was the man himself, seeking respite. She welcomed him and his companions in from the cold.

As the snowstorm raged outside her door, they re-established their brief acquaintance from long ago. We can only imagine how that might conversation might have progressed—him speaking of his time in London, she of her family, and then the Lord’s calling on each of their lives—not to mention what brought them both to America.

The next day, the men worked on clearing a path through the snow, and as Elizabeth was preparing to visit her patients, John asked if he might accompany her in her ministrations. In that event, as John's compassionate nature exhibited itself in the spiritual comfort he offered to the people in her care, she saw him in a more attractive way than ever before. They spent several more days in united efforts together, becoming more thoroughly acquainted as the time passed. But soon he and his friends departed. Then in May, he and some Friends passed by her farm again as they traveled to their quarterly meeting in Salem.

The Haddon land tract lay in an almost unbroken wilderness, where almost nine miles of rivers and dense forest separated the diminutive port city from the place her future home lay. To someone less brave (and perhaps youthful) the prospects of forging her way there and then taming this land might have appeared doleful. But to Elizabeth, even after enduring the travails of an ocean voyage and seeing the largeness of the task before her, she was no less purposeful and determined. She fully accepted the loneliness and inconveniences she must overcome to forge a new home and settlement in such circumstances.

Always too busy to spend time complaining, and daily trusting in her Heavenly Father’s hand, she became known for her graciousness, efficiency, and tirelessness. The Indians in the region trusted her to be truthful, just, and kind, and she, in turn, learned about natural medicines from them. Elizabeth eventually used her knowledge to aid men, women, and children for miles around. In the meantime, wherever she went, she gathered information on ways she might improve her farm, whether it was for better seeding of crops or increasing dairy production. In the meantime, her home became a universal layover for Friends traveling to the Quaker meeting house in Newtown and as a respite for other weary travelers who found themselves at her door.

Such is how she became more thoroughly acquainted with a minister by the name of John Estaugh. With several other Friends, his sleigh approached her home on a brisk winter’s evening. She had met Mr. Estaugh once before, years earlier in London when he preached there, and she was still a child. Now here was the man himself, seeking respite. She welcomed him and his companions in from the cold.

As the snowstorm raged outside her door, they re-established their brief acquaintance from long ago. We can only imagine how that might conversation might have progressed—him speaking of his time in London, she of her family, and then the Lord’s calling on each of their lives—not to mention what brought them both to America.

The next day, the men worked on clearing a path through the snow, and as Elizabeth was preparing to visit her patients, John asked if he might accompany her in her ministrations. In that event, as John's compassionate nature exhibited itself in the spiritual comfort he offered to the people in her care, she saw him in a more attractive way than ever before. They spent several more days in united efforts together, becoming more thoroughly acquainted as the time passed. But soon he and his friends departed. Then in May, he and some Friends passed by her farm again as they traveled to their quarterly meeting in Salem.

It has been suggested that John might have been a bit slow or awkward at courtship. We don’t know for sure, but for whatever reason he seemed reticent, Elizabeth soon took matters into her own hands regarding their friendship. As he prepared to leave again, she stated her case:

(The following is an unauthenticated conversation taken from William Worthington Fowler’s Woman on the American Frontier / A Valuable and Authentic History of the Heroism, Adventures, Privations, Captivities, Trials, and Noble Lives and Deaths of the "Pioneer Mothers of the Republic" (Kindle Locations 2659-2666). Kindle Edition."

“Friend John, I have a subject of importance on my mind, and one which nearly interests thee. I am strongly impressed that the Lord has sent thee to me as a partner for life, I tell thee my impression frankly, but not without calm and deep reflection, for matrimony is a holy relation, and should be entered into with all sobriety. If thou hast no light on the subject, wilt thou gather into the stillness and reverently listen to thy own inward revealings? Thou art to leave this part of the country to-morrow, and not knowing when I should see thee again, I felt moved to tell thee what lay upon my mind."

After schooling his surprise, he said, "This thought is new to me, Elizabeth, and I have no light thereon. Thy company has been right pleasant to me, and thy countenance ever reminds me of William Penn's title-page, 'Innocency with her open face.' I have seen thy kindness to the poor, and the wise management of thy household. I have observed, too, that thy warm-heartedness is tempered with a most excellent discretion, and that thy speech is ever sincere. Assuredly, such is the maiden I would ask of the Lord as a most precious gift; but I never thought of this connection with thee. I came to this country solely on a religious visit, and it might distract my mind to entertain this subject at present. When I have discharged the duties of my mission, we will speak further." "It is best so," rejoined the maiden, "but there is one thing disturbs my conscience. Thou hast spoken of my true speech; and yet, friend John, I have deceived thee a little, even now, while we conferred together on a subject so serious. I know not from what weakness the temptation came, but I will not hide it from thee. I allowed thee to suppose, just now, that I was fastening the girth of my horse securely; but, in plain truth, I was loosening the girth, John, that the saddle might slip, and give me an excuse to fall behind our friends; for I thought thou wouldst be kind enough to come and ask if I needed thy services." They spoke no further upon this topic; but when John Estaugh returned to England in July, he pressed her hand affectionately, as he said, "Farewell, Elizabeth: if it be the Lord's will I shall return to thee soon."

John Estaugh left for England for a short sojourn but, unable to contain his feelings for her, he returned again in September and made haste to Elizabeth’s farm. John Estaugh and Elizabeth Haddon were married forthwith at a Meeting of the Society of Friends without fanfare but for the presence of a few guests including some Indians known to them.

Their love story is immortalized in a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his collection Tales of Wayside Inn.

Soon after their marriage, John became his father-in-law, John Haddon's, business agent in assuming the management of his property in America, which had increased by extensive purchases. The couple also eventually made three visits back to England to see her family, although her father never did set foot in America where his land purchases had drawn his eldest child.

Meanwhile, the farm Elizabeth started flourished and expanded. After being married for twelve years, the couple built a new home, a two-story brick abode within the limits of present Haddonfield.

Throughout her lifetime, while her husband continued his work in the caring for souls, sometimes taking him away from her for long periods of time, Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh continued to stretch out her hand to the poor and needy. It is said, “She was at once a guardian and minister of mercy to the settlement.”

She and John were happily married for forty years, and she survived another twenty years after his death which occurred in 1742 on the Island of Tortola where he was stricken by fever. (Benjamin Franklin later published one of John’s Gospel tracts.) At the end of Elizabeth’s own life, a published testimonial of the meeting of Haddonfield made these beautiful remarks about her life:

She and John were happily married for forty years, and she survived another twenty years after his death which occurred in 1742 on the Island of Tortola where he was stricken by fever. (Benjamin Franklin later published one of John’s Gospel tracts.) At the end of Elizabeth’s own life, a published testimonial of the meeting of Haddonfield made these beautiful remarks about her life:

"She was endowed with great natural abilities, which, being sanctified by the Spirit of Christ, were much improved; whereby she became qualified to act in the affairs of the church, and was a serviceable member, having been clerk to the woman's meeting nearly fifty years, greatly to their satisfaction She was a sincere sympathizer with the afflicted; of a benevolent disposition, and in distributing to the poor, was desirous to do it in a way most profitable and durable to them, and, if possible, not to let the right hand know what the left did. Though in a state of affluence as to this world's wealth, she was an example of plainness and moderation. Her heart and house were open to her friends, whom to entertain seemed one of her greatest pleasures. Prudently cheerful and well knowing the value of friendship, she was careful not to wound it herself nor to encourage others in whispering supposed failings or weaknesses. Her last illness brought great bodily pain, which she bore with much calmness of mind and sweetness of spirit. She departed this life as one falling asleep, full of days, 'like unto a shock of corn fully ripe.'"

|

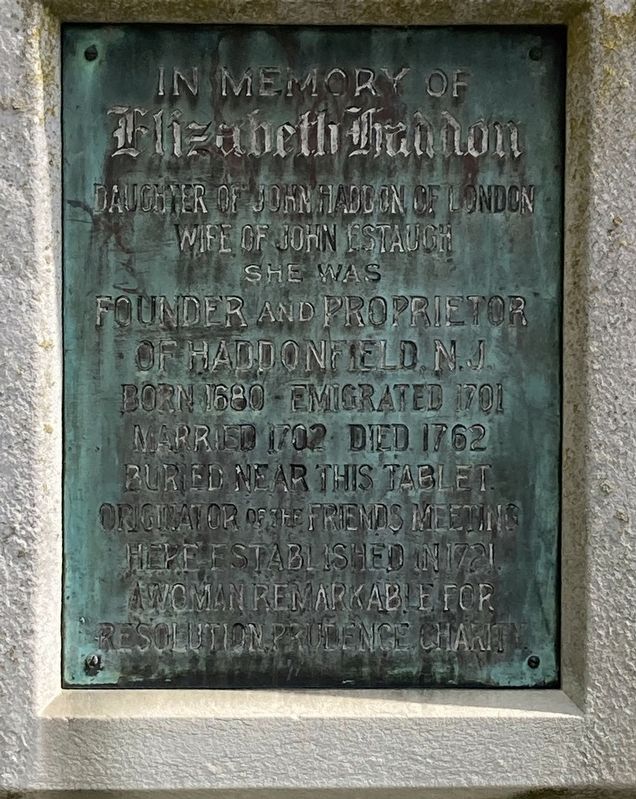

| Photo by Thomas Anderson, Historical Marker Database |

A memorial in Haddonfield, New Jersey bears the inscription:

In Memory of Elizabeth Haddon. Daughter of John Haddon of London. Wife of John Estaugh. She was Founder and Proprietor of Haddonfield N.J. Born 1680- Emigrated 1701. Married 1702 Died 1762. Buried near this tablet. Originator of the Friends Meeting here established in 1721. A woman remarkable for Resolution, Prudence, Charity

______________________________________________________

Paint Me Althena is refreshed and updated!

a Novel of Second Chances

.jpg)

Thank you for posting today. This was a beautiful, touching tribute to a woman who lived life well.

ReplyDeleteWhat a wonderful story! I enjoyed reading it, thank you for telling us about Elizabeth Hadden Estaugh.

ReplyDelete