by Martha Hutchens

|

| MishaAbesadze, Deposit Photos |

At 16, Ted transferred to Harvard as a junior, having already completed two years of college. He was also already active in communist organizations and following the battle between Germany and the Soviet Union closely. In his second year, he was assigned to room with Saville Sax, who would become a lifelong friend and his co-conspirator in spying on the Manhattan Project.

At 18, Ted Hall and his other roommate Roy Glauber were each called to a secretive meeting. Merrill Hardwick Trytten recruited promising young scientists from across the country to work on the Manhattan Project. Of course, he told the young men nothing about the project other than “it was important work which needed more hands.” Later, Sax overheard Glauber and Ted speculating about the project. He mentioned to Ted that “if this (the project) turns out to be a weapon that is really awful, wat you should do about it is tell the Russians.”

|

| image by Martha Hutchens |

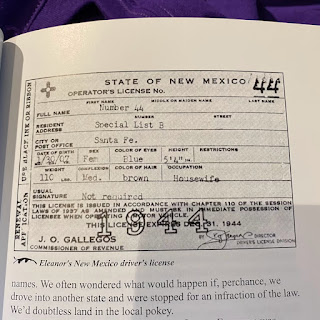

Ted arrived in New Mexico in January 1944. He was 18. When he arrived at Los Alamos, he received a coveted white badge, which meant that no area of questioning was closed to him. He was assigned to learn about the properties of uranium, and eventually worked on determining the amount of uranium needed for a critical mass.

He was also well aware of the problems the Manhattan Project had run into in using Plutonium in an atomic bomb. Uranium occurs in multiple isotopes, but only U-235 can be used in a chain reaction. Separating isotopes is a daunting task, because they are chemically identical. This separation process was developed and performed at Oak Ridge in Tennessee. To give an idea of the difficulty, it is estimated that 10% of the total amount of electricity used by all of the United States when to this project while it was active.

|

| frankie_s, Deposit Photos |

Hall spent a good bit time worrying about the implications of the United States having a monopoly on nuclear weapons. On October 15, 1944, he received leave and traveled to New York, ostensibly to visit his parents. In fact, he planned to contact the Soviets.

During his visit to New York City, he met with his college friend Saville Sax. They discussed several ways for Ted to get his information to the Soviets. First, Sax contacted Artkino, a branch of Soviet cultural propaganda. His story about his teen-aged super scientist buddy who wanted to share top secret information was met with skepticism, to say the least. Ted approached a Soviet trade company and got only a marginally warmer reception. He was given a name and number before he was shooed away.

|

| Wirestock, Deposit Photos |

Kurnakov was a low-level officer without diplomatic cover, so he couldn’t open a permanent channel to Ted Hall. After this meeting, Hall was in a quandary. He had told Kurnakov that any contact in New Mexico would be difficult, if not impossible. Still, the Soviets did not assign him a handler, possibly because they did not trust this whiz kid who came forward without recruitment. Hall and Sax were left to determine their own method of sending information.

They devised a code based on the book of poetry, Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman. In letters, they would quote a line of these poems, and the poem number and line number corresponded to the date they would meet. These letters easily passed through the censorship in Los Alamos.

|

| paulbradyphoto, Deposit Photos |

This was the first information the Soviets received about the problems of a plutonium bomb. They were suspicious of the information until they received confirmation from Klaus Fuchs. At that point, they realized Hall was a trust-worthy source and assigned him a Soviet handler. Hall and his handler met once, on August 6, the same day that Hiroshima was bombed.

Hall left Los Alamos in 1946 and was honorably discharged. He lost his security clearance, not because of his transfer of atomic secrets, but because he changed his field of research.

|

| vampy1, Deposit Photos |

When he first became aware that his name would become public, Hall drafted a document to explain his rationale for his actions. While Hall never released this document, he did give it to the authors of his biography, Bombshell: The Secret Story of America’s Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy. In this document, Hall stated “the situation was far more complicated than I understood at the time, and if confronted with the same problem today I would respond quite differently.”

Martha Hutchens is a transplanted southerner who lives in Los Alamos, NM where she is surrounded by history so unbelievable it can only be true. She won the 2019 Golden Heart for Romance with Religious and Spiritual Elements. A former analytical chemist and retired homeschool mom, Martha is frequently found working on her latest knitting project when she isn’t writing.

Martha’s current novella is set in southeast Missouri during World War II. It is free to her newsletter subscribers. You can subscribe to my newsletter at my website, www.marthahutchens.com

After saving for years, Dot Finley's brother finally paid a down payment for his own land—only to be drafted into World War II. Now it is up to her to ensure that he doesn't lose his dream while fighting for everyone else's. No one is likely to help a sharecropper's family.

Nate Armstrong has all the land he can manage, especially if he wants any time to spend with his four-year-old daughter. Still, he can't stand by and watch the Finley family lose their dream. Especially after he learns that the banker's nephew has arranged to have their loan called.

Necessity forces them to work together. Can love grow along with crops?