When we think of prisoners of war during WWII, we naturally think of death camps, starvation, abuse, and a long season of suffering. We don't usually think about prisoners of war held here in the United States — of Germans and Japanese soldiers sitting out the war on American soil.

Yet, we rarely consider the many thousands of prisoners shipped here from overseas to be incarcerated in camps and the tens of thousands of those men who were sent to work in American fields and factories. Yet they were.

Image by S. Hermann & F. Richter from Pixabay

When I wrote my novel Season of My Enemy which releases on June 1st, I was inspired by many accounts of the lives of those prisoners and of the Americans who were affected by their presence here. Here are just a few of the true stories/incidents that gave me inspiration for my novel:

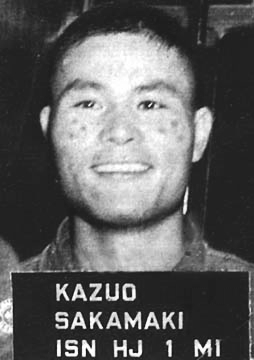

Not to give an incomplete picture, yes, there were Nazis taken as prisoners. Camp McCoy in west-central Wisconsin housed 5000 German prisoners, and some of them were known Nazi sympathizers. The camp also housed 3,500 Japanese and 500 Koreans and a number of Italians also. McCoy even held America's first World war II POW, Kazuo Sakamaki — America’s first World War II POW — captured during Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Sakamaki was a Japanese naval officer whose midget submarine ran aground. Out of the ten men operating five such two-man subs, only Sakamaki survived. After unsuccessfully attempting to scuttle his sub, he collapsed unconscious on a beach where he was found by American soldier David Akui and taken into custody.

Outside of Camp McCoy, however, approximately 13,000 more German soldiers were placed at some thirty-eight make-shift camps all over the state — and this is just speaking of Wisconsin. 511 such camps existed in states all across the Union, camps dedicated to housing prisoners who worked in the agriculture industry. Here, they set to work harvesting all manner of crops including sugar beets — a critical commodity used for making the industrial alcohol needed to manufacture munitions and synthetic rubber.

- Clem Batz of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin watched the prisoners work. He said, “I was about 11 years old at the time, so it would have been 1945. There was a crew of German prisoners for the farm, and the fellows picked the corn by hand. It was all picked by hand ‘til the 50s, so they’d pick the corn and throw it in the wagon. At noon, they’d bring lunch for them (from the branch camp) and they’d always bring a guard. That was kind of funny because they never had a guard while working. My dad spoke German fluently, and he’d have them quit a little early to relax and visit a little bit.”

- Ruth Barrette was a teenager during the summer of '45 she spent picking cherries with German prisoners — boys about her own age — in her family’s orchard. She called that season a turning point in her life. As pails filled with ripe fruit, the boys shared with her the longing they had of returning home to families torn apart by a war they never asked for. Residents of rural farm communities like the one where Miss Barrette lived soon came to learn the German prisoners who were allowed to work were not Nazis at all, but young men and boys drafted into Hitler's reign of terror. Here in Wisconsin, where about a third of the population is of German descent, many of those prisoners might have been distant relatives, a fact that was not lost on Wisconsinites.

- Unlike what Japanese-Americans endured in the western coastal states, the German prisoners in the upper Midwest were treated with a certain degree of hospitality. David Rumachik, a preteen at the time, remembered his father hiring German men and boys as young as thirteen to pick their family's 60 acres of tomatoes. He said, “My mother talked to them and set out bowls of fruit for them. They were people, just like us, so it was hard for me to look at them and think that they were the enemy."

- In my coming novel, Fanny O'Brien's mother sets out lunch for the prisoners and sometimes gives them slices of baked bread after working the pea harvest. That bit of inspiration came from situations like that of Marge Lind who recalls her father hiring workers to help with the pea harvest on the Linds' farm. Due to a lack of the usual migrant workers during the war, the soldiers who were housed in a large cattle barn near the Baptist Church were trucked in to work the fields. The POWs cut and loaded pea vines onto a truck sent to the viners. Then the peas would be gleaned off and shipped on to a local cannery. Lind said that at noon the men gathered at the family's dooryard where lunch was served. "They were just teenage boys, nice kids that my mother baked bread for,” she said in later life. “For years my folks got letters from some of the boys after they returned home. There was that kind of a connection.”

- Another woman whose mother grew up during that time states, "My mother lived at Mike Miller's orchard/picking camp as a girl. Her dad managed it. She has always told us stories of talking with these men behind the fence. They would show her pictures of their own children and get teary-eyed. If grandma baked cookies the girls would sneak them through the fence. When the men were gone working in the orchard, grandpa would take the girls in the mess hall to sweep and clean."

- Military chaplains or local ministers held services for German prisoners, and it was not uncommon for nearby congregations to allow military guards to truck PWs to services. Be that as it may, the army kept most prisoner locations on the low-down, as not not everyone was keen on having the prisoners in their areas or working alongside American men and women in their communities. Many American soldiers who fought in horrible conditions overseas or were captured themselves, gave a good deal of kickback in their opinions about the supposed "cushy life" of the German prisoners. After the war, many records from the camps were destroyed.

In an effort to protect photograph copyrights, I don't include a lot of pictures in this post, but here's a link to 22 historic photos of German soldiers who worked in Wisconsin's fields and factories during WWII and formed relationships with citizens, including a photograph of Kurt Pechmann whose story I share below.

Sakamaki in U.S. custody

Outside of Camp McCoy, however, approximately 13,000 more German soldiers were placed at some thirty-eight make-shift camps all over the state — and this is just speaking of Wisconsin. 511 such camps existed in states all across the Union, camps dedicated to housing prisoners who worked in the agriculture industry. Here, they set to work harvesting all manner of crops including sugar beets — a critical commodity used for making the industrial alcohol needed to manufacture munitions and synthetic rubber.

- Probably one of the most well-known accounts of a German prisoner, one that had a strong influence on my novel Season of My Enemy, is the story of Kurt Pechmann, a German granite cutter who had been drafted into the army and assigned the inglorious task of digging ditches. When his infantry division was moved to Russia, he said that lice helped keep them awake and alive as temperatures fell as low as eighty below zero. After surviving frostbite and being transferred to Italy, he stole olives to survive, but he was eventually captured by British forces. Because he'd always been told and believed that Americans, British, and Russians were bad, he was convinced he must be a Nazi. However, after arriving in the U.S. and enjoying his first meal of smoked bacon and "bread that tasted like cake", he began noticing the differences in life from what he'd always been told.

Sent to work in a Wisconsin canning factory along with his fellow prisoners, he enjoyed coffee and chocolate donuts topped with sprinkles as a snack handed out to those working the midnight shift. Working on a farm, he and his fellows were complimented for their work ethic, given a feast from the farmer, and in another town a truck even brought them a keg of beer once a week.

Kurt Pechmann in Camp Hartford in 1945

Many prisoners shared a camaraderie with the guards, were allowed to form soccer teams, and even enjoyed films which at first consisted of propaganda but later included popular entertainment. Some even took college courses and acquired degrees.After the war, all prisoners were repatriated back to Germany, but as many as 5000 Germans who'd previously been prisoners like Pechmann emigrated back to America through proper channels, and their descendants live here today.

After Pechmann was repatriated, he married and came back to America with his new wife Emilie. Here, he established himself as a businessman in stone masonry and memorials. Along with creating tombstones, he also went on to build and repair monuments to American veterans. He was later recognized in a letter from President Ronald Reagan and given an honorary Purple Heart.

WHAT ABOUT SABOTAGE AND TROUBLE-MAKERS?

In my research, I discovered that only compliant prisoners were allowed to work outside of the main or branch camps. Within the branch camps themselves, comrades disciplined trouble-makers. As in my novel, some prisoners might stage work stoppages for some reason, but only a very few made attempts at sabotage or escape. Usually, if there was an escape, it turned out to be one or two men who walked off the compound in search of a beer or some women.

The more sensible prisoners preferred being well-fed, well-treated, and not being shot at. Some guard did uncover weapons such as wire cutters, hand saws, hammers, knives, or sharpened screwdrivers. If an undetected SS officer joined other PWs, he usually tried to stir up trouble and resistance. (Another inspiration for my story.) Trouble-makers were usually quickly spotted and rooted out.

MY NOVEL IS ROMANTIC, BUT DID AMERICAN WOMEN REALLY FALL FOR PRISONERS?

Well, you tell me. I'll point out that it was illegal for a POW to marry in the U.S.; however, after the war Washington enabled the fiancés of former POWs to set sail for Italy on surplus troop transports with a chaperone such as an aunt or mother. Each war bride carried two trunks of personal luggage along with the documents required for a legal marriage in Italy. By marrying in Italy, the women could then legally bring their new husbands back to America to live. Do you think that answers the question?

So is there a small, rosy side to WWI history? While I don't under-emphasize the horrors and atrocities of that or any war (including in my novel), to see that in at least one small aspect there was a time and place where people remembered that their enemies were human beings with hearts as aching and wanting as their own, well . . . that is a good thing.

With that, I'll conclude. Here are a few other resources I used while writing my novel, which may interest you also:

"Stalag Wisconsin: Inside WWII Prisoner-of-War Camps" by author Betty Cowley features more than 350 interviews, and serves as a comprehensive history of Wisconsin camps. This book was a real treasure as I wrote Fannie's story.

An article that encapsulates much of the German POW experience:

Washington Post: Enemies Among Us: German POWs in America

For my fellow Wisconsinites, here is a list of all the WWII branch camps in Wisconsin and their locations.

For my fellow Wisconsinites, here is a list of all the WWII branch camps in Wisconsin and their locations.

Season of My Enemy

The realities of WWII come to a Wisconsin farm bringing hope and danger.

Only last year Fannie O’Brien’s future shone bright, despite the war pounding Europe. Since her father’s sudden death however, with one older brother captured and the other missing, Fannie has had to handle the work of three men on their 200-acre farm, with only her mother and two younger siblings to help. That is until eight German prisoners arrive as laborers and, as Fannie feared, trouble comes with them.

Crops take precedence, even as accidents and mishaps happen around the farm. Are they leading to something more sinister? Suspicion grows that a saboteur may be among them. Fannie is especially leery of the handsome German captain who seems intent on cracking her defenses. Can she manage the farm and hold her family together through these turbulent times, all while keeping the prisoners—and her heart—in line?

Keep updated on Season of My Enemy and my other books, and get in on some monthly drawings by signing up for my newsletter right here.

Thanks for posting this thoughtful, insightful article. I really liked hearing about the kindnesses extended to the prisoners. I'm sure there are stories of our soldiers finding mercy in their circumstances as POWs overseas, it would be nice to highlight some of those as well. Maybe another participant in the blog will do that, I do remember some having posted stories like that already.

ReplyDeleteI love learning about these little-known facets of history. In my novel there is mention of a kindness by a German guard in an overseas POW camp. That, to me, has been one of the interesting tidbits of history, amidst all the horror and tragedy and evils that lurk in the hearts of many.

DeleteThis was so interesting. Helping in agriculture seems a safe occupation that kept them away from any activity that might give the enemy military intel. I had no idea there were so many camps in the Midwest. Apparently the farming community my dad grew up in Southern Illinois had none. My husband worked with a woman's whose husband was in a a German POW camp and he was angry that his wife lent his golf clubs to a German officer in a POW camp near their home. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteWe had a prison camp in my home town, and I never heard of it growing up. Didn't learn about it until researching my novel. I was shocked. Neither of my parents knew about it either, yet those prisoners were sent out to work on the cranberry bogs with the locals and in the canneries. VERY interesting about the woman your husband worked with. Yes, there was a lot of anger at people who reached out in any small way.

Delete