By Kathy Kovach

Do you love to walk? Around the neighborhood. A nature hike. Perhaps you even have aspirations of taking on the Appalachian Trail, which is comprised of 2,200 miles between Georgia and Maine. But have you ever thought of walking around the world?

Backward?

Thirty-six-year-old Plennie Lawrence Wingo did. Born in 1895, the café owner found himself a victim of the Great Depression, his business succumbing to failure. He turned to entertainment, thinking he could bring in extra cash by learning how to walk backward at a fast pace. The world tour idea came about when his 15-year-old daughter hosted a party, and one of the boys mentioned some of the feats performed by adventurers, such as Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, the spectacle of flagpole sitting, or the person who pushed a peanut up Pike’s Peak with his nose. All that could be done had already been done, he opined. “Ah,” Wingo may have said. “But what about someone walking backward around the world? No one has tried that.”

Backward walking wasn’t a new thing, however. Several people had taken on the challenge, some at great distances. But none had attempted a transcontinental reverse stroll.

July 11, 1817 – Darby Stevens set off from Wormwood Scrubbs, England intent on walking backward for 500 miles in 20 days. He did it on a wager for 50 guineas. It’s unclear if he actually made it.

Others followed suit, even into the next century. One such fellow was arrested in New Jersey for walking backward into people’s homes to beg. He was Spaniard Paul Guavarra, who claimed to be descended from Christopher Columbus. True to form, he walked backward into his jail cell.

Patrick Harmon of Seattle sold his cigar shop after being fined $100 for gambling. Ironically, he decided to walk on a bet of $20,000 on August 5, 1915, from San Francisco to New York with his friend and guide, William Baltazor, who he paid $4 a day. They made the journey successfully, and “paraded up the steps of City Hall. . .walking backward. . .” a New York newspaper touted. Some controversy ensued over whether the duo followed the rules, even though Harmon suffered frostbite on the tips of his ear and nose during January in Iowa. They also claimed to have battled a rabid coyote in Nevada, although the area they claimed it happened in was inconsistent. They were no doubt on the railway line rather than the Lincoln Highway, apparently taking trains throughout Nevada. Turns out Patrick Harmon of Seattle was really Patrick O’Rourk from St. Mary’s, Ohio, and had been living under an alias. No wonder there were trust issues. Whether he won the wager was never reported.

Jackson Corwin, later known as the Human Crawfish, was mistaken for a detective as he made his reverse way from Philadelphia to San Francisco in 1923. One woman gave him her husband’s picture and asked him to keep an eye out for him.

No one in their right mind would take on a world walking tour. Without a dime in their pocket. During the Great Depression. Backward.

No one but Plennie Wingo.

Wingo practiced until he felt it time to go public, which he did at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth, Texas on March 7, 1931. First, he walked around town advertising the stock show. This earned him the right to present himself during the show. Wearing a cowboy costume and a sign on his back that now billed himself as “the first reverse walker of the world,” he strutted, toe over heel.

And thus, on April 15, 1931, he said goodbye to his wife and daughter. It comes as no surprise that Mrs. Idella Wingo was not on board with this stunt. Even so, he donned eyeglasses with mirrors incorporated in the sides, and began his expedition, one foot behind the other.

When he reached Dallas, he stopped at a photography studio to take his picture and have postcards made that he could sell along the way. He continued to wear his sign on his back. A policeman stopped him, stating an ordinance prohibiting the carrying of signs of any type. Wingo found a phone and called the mayor. After explaining his plight, the mayor granted permission. Other towns presented the same struggle, some over the signage and some over concern about the backward walking, but Wingo simply talked to those higher up and was granted passage.

Wingo didn’t have to walk backward all of the time. When he entered a town, he’d find the Western Union and have his book stamped for proof of day and time. Then, he was free to walk normally around town. This elicited some booing from the crowds gathered until he assured them all was on the up and up. If he was forced to move forward at any time, he would note where it happened and return to the place of interruption to continue on. He refused to cheat, just as he was determined to earn his own way. The postcard sales assisted with food and lodging, and the occasional sign advertising for businesses helped.

Although adept at reverse walking, Plennie wasn’t impervious to injury. On July 30, after 1700 miles, he stepped in a hole near Canton, Ohio, and fractured his ankle. He spent three weeks recovery time in the hospital free of charge. He’d become somewhat of a celebrity by this time, with his story featured in a newsreel that was seen in theaters. Go here A Texan man during his round the world walking tour in Chicago, Illinois. HD Stock Footage - YouTube to see it.

Once fully recovered, Wingo recommenced on August 24, 1931. Another policeman approached him as he was leaving a city in Pennsylvania. He issued him a citation for “mopery in the second degree,” but the ticket read, “Good luck on your trip around the world.”

Although Idella Wingo had been writing letters to Plennie, they dried up after fifty days. When she finally wrote again, it was to ask him to give up and come home. His daughter also wrote telling him her mother was ill. They’d been trying to make a go of it, but without money coming from him, it was hard. Wingo was devastated but refused to quit.

His walk stalled in mid-October when he reached New York City. Despite handing out business cards describing his desire, he still had no sponsor to help him get to Europe. The urge to give up became strong. He stayed in a boarding house and took on jobs. Two-and-a-half months later, in December, he decided to continue on and left for Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Another letter caught up with him, this time with divorce papers, which he signed.

At long last, on January 12, 1932, a shoe company found work for Wingo as part of the crew aboard the Seattle Spirit, a merchant ship traveling to Germany. He walked the gangplank backward. However, seasickness overcame him the first five days. When they docked in Hamburg, the steward, who had been cruel to him for the entire journey, refused to let him leave. Wingo snuck off the boat about three weeks later when the steward was gone. Months later, a letter reached Wingo from a shipmate revealing what happened after he disembarked. It seemed the steward came on board about nine o'clock that night, happy to discover that Wingo was gone. He took a bath and headed to bed. In about twenty minutes, he was heard screaming, hollering, and cursing. His skin was red and itching, he felt he was on fire. After a search of his bed, it was discovered lye had been the culprit. Wingo had been in charge of the laundry, and he'd gotten his final revenge.

Plennie Wingo's call to adventure doesn't stop here. Join me next month for Part II, Europe. Does he make it all the way around the world? What challenges will he face in pre-World War II Germany? What about the Eastern European block? Trust me when I say, you don't want to miss it.

Follow two intertwining stories a century apart. 1912 - Matriarch Olive Stanford protects a secret after boarding the Titanic that must go to her grave. 2012 - Portland real estate agent Ember Keaton-Jones receives the key that will unlock the mystery of her past... and her distrusting heart.

Kathleen E. Kovach is a Christian romance author published traditionally through Barbour Publishing, Inc. as well as indie. Kathleen and her husband, Jim, raised two sons while living the nomadic lifestyle for over twenty years in the Air Force. Now planted in northeast Colorado, she's a grandmother, though much too young for that. Kathleen is a longstanding member of American Christian Fiction Writers. An award-winning author, she presents spiritual truths with a giggle, proving herself as one of God's peculiar people.

Wingo practiced until he felt it time to go public, which he did at the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show in Fort Worth, Texas on March 7, 1931. First, he walked around town advertising the stock show. This earned him the right to present himself during the show. Wearing a cowboy costume and a sign on his back that now billed himself as “the first reverse walker of the world,” he strutted, toe over heel.

And thus, on April 15, 1931, he said goodbye to his wife and daughter. It comes as no surprise that Mrs. Idella Wingo was not on board with this stunt. Even so, he donned eyeglasses with mirrors incorporated in the sides, and began his expedition, one foot behind the other.

|

| The .25 postcard that helped finance the walk around the world. |

When he reached Dallas, he stopped at a photography studio to take his picture and have postcards made that he could sell along the way. He continued to wear his sign on his back. A policeman stopped him, stating an ordinance prohibiting the carrying of signs of any type. Wingo found a phone and called the mayor. After explaining his plight, the mayor granted permission. Other towns presented the same struggle, some over the signage and some over concern about the backward walking, but Wingo simply talked to those higher up and was granted passage.

Wingo didn’t have to walk backward all of the time. When he entered a town, he’d find the Western Union and have his book stamped for proof of day and time. Then, he was free to walk normally around town. This elicited some booing from the crowds gathered until he assured them all was on the up and up. If he was forced to move forward at any time, he would note where it happened and return to the place of interruption to continue on. He refused to cheat, just as he was determined to earn his own way. The postcard sales assisted with food and lodging, and the occasional sign advertising for businesses helped.

Although adept at reverse walking, Plennie wasn’t impervious to injury. On July 30, after 1700 miles, he stepped in a hole near Canton, Ohio, and fractured his ankle. He spent three weeks recovery time in the hospital free of charge. He’d become somewhat of a celebrity by this time, with his story featured in a newsreel that was seen in theaters. Go here A Texan man during his round the world walking tour in Chicago, Illinois. HD Stock Footage - YouTube to see it.

Once fully recovered, Wingo recommenced on August 24, 1931. Another policeman approached him as he was leaving a city in Pennsylvania. He issued him a citation for “mopery in the second degree,” but the ticket read, “Good luck on your trip around the world.”

Plennie, Idella, and Vivian during the normal years.

Although Idella Wingo had been writing letters to Plennie, they dried up after fifty days. When she finally wrote again, it was to ask him to give up and come home. His daughter also wrote telling him her mother was ill. They’d been trying to make a go of it, but without money coming from him, it was hard. Wingo was devastated but refused to quit.

His walk stalled in mid-October when he reached New York City. Despite handing out business cards describing his desire, he still had no sponsor to help him get to Europe. The urge to give up became strong. He stayed in a boarding house and took on jobs. Two-and-a-half months later, in December, he decided to continue on and left for Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Another letter caught up with him, this time with divorce papers, which he signed.

At long last, on January 12, 1932, a shoe company found work for Wingo as part of the crew aboard the Seattle Spirit, a merchant ship traveling to Germany. He walked the gangplank backward. However, seasickness overcame him the first five days. When they docked in Hamburg, the steward, who had been cruel to him for the entire journey, refused to let him leave. Wingo snuck off the boat about three weeks later when the steward was gone. Months later, a letter reached Wingo from a shipmate revealing what happened after he disembarked. It seemed the steward came on board about nine o'clock that night, happy to discover that Wingo was gone. He took a bath and headed to bed. In about twenty minutes, he was heard screaming, hollering, and cursing. His skin was red and itching, he felt he was on fire. After a search of his bed, it was discovered lye had been the culprit. Wingo had been in charge of the laundry, and he'd gotten his final revenge.

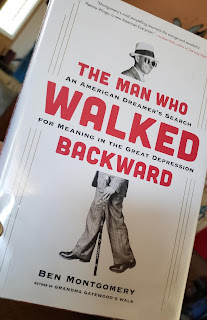

The backward walk heard around the world began on the nineteenth anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, April 15, 1912. No mention of this important time in history is given in the account from the book pictured above, The Man Who Walked Backward, by Ben Montgomery. It could be that the Great Depression was pressing hard on the nation, making all other watersheds pale in comparison. Even so, Montgomery paints the backdrop with historical moments so as to capture every nuance of what Plennie Wingo walked through.

Backward.

A secret. A key. Much was buried on the Titanic, but now it's time for resurrection.

To buy: Amazon

Thanks for posting. What a bizarre story! I'm anxious to read more next month.

ReplyDelete