by Jennifer Uhlarik

Hello, readers! Are you ready for more interesting history about the oldest masonry fort on U.S. soil? If you’ve been following along, you’ve learned all about the fort’s founding and how it was passed between Spain, Britain, Spain again, the United States, and even fell to the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. Last month, I told you how, for a period of three years during the 1870s, the fort became home to seventy-three Plains Indians. And this month, I’ll share another interesting chapter of the Castillo’s history—the internment of the Apache Indians.

Just as we learned in last month’s post about the Plains Indians, the Native Americans of all tribes were struggling to acclimate to the idea of so many white men flooding into what had been their traditional territories. The Apaches were no different, and conflicts sparked between these groups all across Arizona for decades. Fierce warriors that they were, the Apaches fought hard against the incoming settlers, making homesteading in the Southwest a difficult endeavor. The Frontier Army came in and attempted to subdue the Apaches, placing them on reservation lands, but as so often happened, those promised lands ended up being found to have hidden value in the form of gold, silver, or other resources. Or the government didn’t deliver the promised supplies—cattle and other food supplies, blankets and clothing, etc. So new treaties were negotiated, and new boundaries drawn up, shrinking the sizes of reservations or moving them to new locations all together, all so that white men could capitalize on the resources they’d found on reservation lands—or with more promises of better supplies in the new locales. As anyone would, the Apaches grew tired of this shuffling and broken promises. Bands began breaking out of the reservations to go again on raids and make war on the Army and settlements for these unfair practices, as well as to provide for their families. Ultimately, this war went on for years, but slowly ended as Apache leader after Apache leader finally surrendered when they couldn’t keep going.

|

| Apache Men sitting among cannons housed at Fort Marion, circa 1886 |

As you might imagine, life was difficult in a strange new place, particularly in such tight quarters. The Apaches were given a pound of beef per adult per day, with children receiving half that; fresh bread each day; vegetables and grains like rice, turnips, hominy and beans, as well as a small weekly portion of potatoes and onions. The women were expected to cook the food themselves, except for the bread, which was made down the street at St. Francis Barracks and carted over each morning. They drank coffee with sugar, or they had water from the well within the fort’s walls.

|

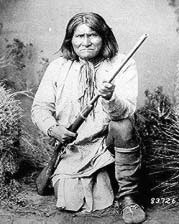

| Geronimo, one of the most famous Apache warriors. While he was not held at Fort Marion, his wife was, and gave birth to his daughter, Marion (later renamed Lenna), while there. |

There were twelve Apache children born during the year they were incarcerated at Fort Marion, the first of which was Geronimo’s daughter (aptly names “Marion”, although she later changed her name to Lenna). Unfortunately, there were also several deaths in that year. When you stop to consider the sheer number of people in such confined spaces, it isn’t surprising that illness ran rampant among them. Colonel Langdon, who was in charge of overseeing the Apache prisoners, brought in Army physician, Dr. DeWitt Webb, to treat the men, women, and children. Despite his best efforts, Dr. Webb reported that he lost numerous patients to various diseases, such as dysentery, acute bronchitis, marasmus (or wasting disease), old age, epilepsy, tuberculosis, and neonatal tetanus. All told, twenty-four Apaches died during that year in St. Augustine.

In order to make more room during the daylight hours, the Apaches were allowed to spread out outside the fort walls on the grounds and go into town, but even so, there wasn’t much for them to do. Children played games while the adults saw to the needs of their families, cooking, mending clothing, and repairing their few belongings. There wasn’t enough space for much else. The women would weave baskets to sell to locals and tourists, and men and boys would make and sell bows and arrows, as well as offer lessons in how to use the weaponry. However, with the overcrowded conditions, it was harder for the Apaches to make and sell their wares than it had been for the seventy-three Plains Indians a decade before.

The prisoners began turning to gambling and card games to pass the time until Colonel Langdon came to the same conclusion that his predecessor, Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, had. They needed stimulation, and it would come through education and assimilation. Colonel Langdon contacted Richard Henry Pratt in Carlisle, PA, to ask him to return to Fort Marion and interview the children to see if any would be a good fit at the Carlisle Indian Residential School, of which Pratt was the founder and headmaster. Upon Pratt’s visit, he selected 103 of the children to return with him to the school, and they young ones were immediately sent on their way under Pratt’s care. At the Carlisle Indians School, they children were given military-style uniforms to wear, their hair was cut short, and they were given Christian names.

Apache children in traditional garb on their arrival at Carlisle Indian School (left).

Many of the same children after receiving haircuts and military-style uniforms (right).

Of the roughly four hundred remaining Apaches, Colonel Langdon again called upon St. Augustine’s women to begin educating the Natives. Just as with the Plains Indians, Miss Sarah Mather and other local women set up classes so the Apache adults could learn to read, write, and speak English, as well as some simple arithmetic, science, and other subjects. Those children who were not taken to Carlisle, PA, were taken each weekday to a local nunnery where the Sisters of St. Joseph educated them in similar subject matter. Unlike Lt. Pratt before him, Colonel Langdon did not implement a physical training program or having skilled craftsman teaching the Apaches their crafts—more than likely because there were too many prisoners and not enough space for such education.

After roughly one year, those Apaches left in St. Augustine were moved again, this time to a reservation in Alabama, and later to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, where they remained.

Award-winning, best-selling novelist Jennifer Uhlarik has loved the western genre since she read her first Louis L’Amour novel. She penned her first western while earning a writing degree from University of Tampa. Jennifer lives near Tampa with her husband, son, and furbabies. www.jenniferuhlarik.com

AVAILABLE NOW!

Love's Fortress by Jennifer Uhlarik

A Friendship From the Past Brings Closure to Dani’s Fractured Family

When Dani Sango’s art forger father passes away, Dani inherits his home. There, she finds a book of Native American drawings, which leads her to seek museum curator Brad Osgood’s help to decipher the ledger art. Why would her father have this book? Is it another forgery?

Brad Osgood longs to provide his four-year-old niece, Brynn, the safe home she desperately deserves. The last thing he needs is more drama, especially from a forger’s daughter. But when the two meet “accidentally” at St. Augustine’s 350-year-old Spanish fort, he can’t refuse the intriguing woman.

Broken Bow is among seventy-three Plains Indians transported to Florida in 1875 for incarceration at ancient Fort Marion. Sally Jo Harris and Luke Worthing dream of serving on a foreign mission field, but when the Indians reach St. Augustine, God changes their plans. However, when Sally Jo’s friendship with Broken Bow leads to false accusations, it could cost them their lives.

Can Dani discover how Broken Bow and Sally Jo’s story ends and how it impacted her father’s life?

Thanks for posting today! In hindsight there is much that could have been done differently, but the history is what it is. We move forward and do better, hopefully.

ReplyDelete