By Mary Dodge Allen

His Cherokee name was Sikwayi, but he is best known by the name Sequoyah. He was born in Tuskegee, a Cherokee town in present-day Tennessee, in 1774 or 1775.

Early Years:

His mother, Wuh-teh, was a member of the Cherokee Nation’s Red Paint Clan and his father was a fur trader named Nathaniel Gist. Although Sequoyah was given an English name at birth, George Gist, he was raised solely by his mother, and he spoke only the Cherokee language, even though he knew some English.

Sequoyah had a slight limp, due to a shrunken leg. Despite this, he maintained an active life, and he was a quick learner. He became a successful fur trader. And later on, he became a self-taught blacksmith and silversmith. He even created his own tools and forge.

War of 1812:

Sequoyah served in the Cherokee Regiment of the U.S. Army during the War of 1812. Historians speculate that during the war, he saw the value of papers containing the written form of the English language, which the Cherokees called “Talking Leaves.”

Sequoyah probably observed the paper messages and troop orders that were relayed back and forth. He must have also seen American soldiers writing letters to loved ones, and he was probably touched to see the joy on the faces of the soldiers whenever they received letters from home.

Developing the Written Symbols:

After the war, Sequoyah married and settled in a Cherokee settlement in present-day Alabama. He was convinced a system of writing would benefit his people, and he set out to develop a writing system for the Cherokee language in his spare time. Sequoyah began by experimenting with pictographs, devising an image for each word, but he found this system was too cumbersome to be practical.

He then switched to a phonetic system. Sequoyah listened carefully to the sound patterns of Cherokee words and matched symbols to these basic sounds. The work was tedious. And as the years passed, his determination to create a writing system became an obsession, causing him to neglect his family. It is said that his wife got so fed up, she even burned some of his work papers.

The following is an excerpt from the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 11, No. 1; “Captain John Stuart’s sketch of the Indians.”

“He [Sequoyah] was laughed at by all who knew him, and was earnestly besought by every member of his own family to abandon a project which was occupying and diverting so much of his time from the important and essential duties which he owed his family.”

Finally... Success!

In 1821, after twelve years of work, Sequoyah succeeded in creating a written system known as a syllabary – a set of 86 symbols that represent every spoken syllable in in the Cherokee language. He was overjoyed when he saw how easily he could teach this system to his six-year-old daughter, A-yo-ka.

Life or Death - Witchcraft Trial:

As word spread about Sequoyah’s syllabary, Cherokee leaders accused Sequoyah and his daughter of witchcraft and put them on trial before the Chief. They believed this written system of communication was a form of magic or sorcery. If Sequoyah and his daughter were found guilty of witchcraft, they would be put to death.

During the trial, Sequoyah and A-yo-ka were separated. Sequoyah was then forced to write a specific message to his daughter, using the syllabary. When A-yo-ka appeared before the Chief and successfully read the message her father had written, everyone was astonished.

Some still believed it was witchcraft. But in the end, the Chief decided Sequoyah had truly found a way to represent words on paper. Soon, tribal members began asking Sequoyah to teach them to read, including the leaders who had put him on trial!

Literacy Spreads throughout the Nation:

Sequoyah had tailored his syllabary to the specific sounds of the Cherokee language, which made it relatively easy to learn. Over the next few years, a significant number of the Cherokee population became literate.

Sequoyah even traveled west of the Mississippi River to teach his syllabary to Cherokees in present-day Arkansas. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation formally adopted his syllabary, and its use became even more widespread.

The Cherokee Phoenix Newspaper:

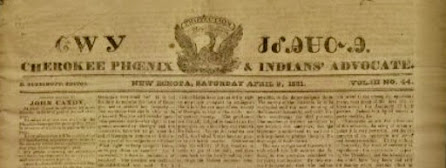

In 1828, a Christian missionary named Samuel Worcester obtained a printing press. He and a Cherokee named Oowatie established a newspaper called the Cherokee Phoenix. It was first published on February 21,1828 in New Echota, capital of the Cherokee Nation in present-day Georgia. This was the first bilingual newspaper in U.S. history.

During his ministry, Samuel Worcester used the syllabary to translate the Bible. He became an active champion for Cherokee rights, and they honored him with the Cherokee name, A-tse-nu-tsi, which means “messenger.”

Trail of Tears:

The Cherokee Phoenix, along with personal written messages, helped the Cherokee Nation to retain a measure of cultural solidarity during the forced migration caused by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. They lost their land, their homes, and many lost their lives as they migrated along the Arkansas River, on what became known as the Trail of Tears. But through the use of the syllabary, members of the Cherokee Nation were able to communicate with each other and keep informed, despite their tragic disbursement.

Sequoyah's Later Life:

During his lifetime, Sequoyah remained faithful to Cherokee traditions and never adopted American clothing or customs. He always focused on what he could do to help the Cherokee Nation.

In 1842, Sequoyah traveled to Mexico to find any tribal members who had migrated there, in hopes of persuading them to return to the Cherokee Nation. While there, he contracted a severe illness. Sequoyah died in August 1843, near San Fernando, Mexico.

His Legacy:

Sequoyah’s Cherokee syllabary, referred to in the Cherokee language as Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, remains in use to this day. It is seen on street signs and buildings across the Cherokee Nation (located in northeastern Oklahoma). The syllabary is also taught to students in schools and universities in Oklahoma and North Carolina.

The impact of Sequoyah’s syllabary spread to other cultures around the world, influencing them to develop their own syllabaries. This includes the Cree syllabary used by the First Nations people in Canada and syllabaries used in West Africa and China.

His syllabary is an accomplishment that greatly helped the Cherokee Nation. Sequoyah's life illustrates that one person’s vision, determination and hard work can make a positive difference in our world.

_________________

Mary Dodge Allen is currently finishing her sequel to Hunt for a Hometown Killer. She's won a Christian Indie Award, an Angel Book Award, and two Royal Palm Literary Awards (Florida Writer's Association). She and her husband live in Central Florida. She is a member of American Christian Fiction Writers and Faith Hope and Love Christian Writers.